What should Australian business do about…

its waning influence on Australia-PRC relations?

By Michael Clifton

Australian business leaders have been overly cautious in their response to the crisis in Australia’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Amidst a rising tide of hostility toward the PRC, they are largely silent or their words are being drowned out by louder voices. Australian business knows it will suffer if there is a long-term freeze in the relationship with the PRC. But unless it speaks more assertively about the benefits of Australia PRC trade, this will be the outcome.

President Xi Jinping and his “wolf warrior” diplomats make it challenging for even the most moderate of Australian voices to call for sensible engagement with the PRC. The aggressive nationalism on display in Hong Kong, on the India PRC border, in Xinjiang and in the South China Sea signal that the PRC leadership regards global approval as less important than issues key to the domestic legitimacy of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

Canberra is uncomfortably wedged between an erratic US ally and a more assertive trade and investment partner.

The PRC may be a diplomatic challenge, but Australian business can ill-afford to stand silent and leave others to shape a new, more hostile approach to dealing with our most critical trade and investment partner. A better balance between security and commercial interests requires that Australian business leaders improve their waning influence on relations with the PRC

To effectively articulate the interests of business in the Australia-PRC relationship, Australia needs a more proactive China business lobby group and a new or revitalised bilateral business-to-business dialogue. In pressing for an improved trade and investment climate, business should not ignore legitimate security concerns that a more assertive PRC gives rise to.

Business interests are national interests

“Listen to business executives on the specifics of their industry but don’t ever let them set the tone politically for the relationship. Their political judgment is rotten and they generally have no very deep institutional commitment to liberal democratic values”

Greg Sheridan, The Australian,

25 October 2019

Media commentators and defence and security analysts do not have a monopoly on the political judgement required to manage relations with the PRC. They simply have a different view. Australian business has the right and the obligation to be heard on the PRC relationship.

Commercial self-interest and the national interest are not mutually exclusive. PRC demand for Australian goods and services remains strong. While our exports of iron ore are most notable, we should not forget the thousands of otherwise unremarkable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) whose livelihoods depend on the PRC – citrus growers, winemakers, lobster fishermen, beef and dairy farmers, tourism operators, and many more. Their success is hard-won and a key driver of national prosperity.

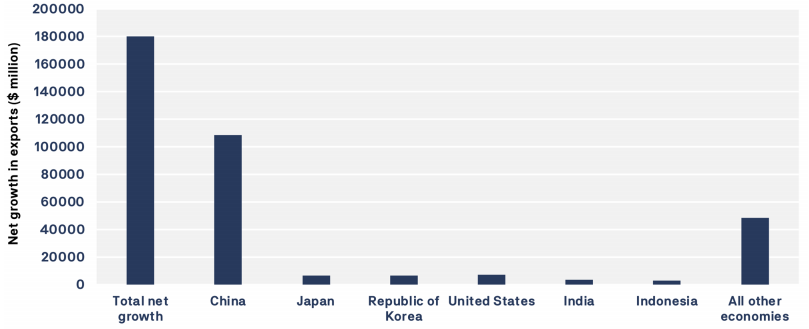

Export destination by contribution to net growth in Australia’s total exports 2008-09 – 2018-19

Source: James Laurenceson and Michael Zhou, Australia-China Relations Institute, ‘COVID-19 and the Australia-China relationship’s zombie economic idea’

In the decade ahead, the PRC is likely to remain the principal engine of global economic growth. Australia’s ability to extract full value from the PRC growth story may be at risk unless Beijing and Canberra are able to repair a fractured relationship.

The business community must do more to highlight the PRC’s contribution to our national prosperity. In doing so, it deserves far better than to be airily dismissed as a greedy, self-interested “pro-Beijing lobby”. As former Secretary of Defence Dennis Richardson observed:

“It is in our interests that quality Australian businesspeople are involved in Chinese investment and companies. ‘Links’ or ‘connections’ to the Chinese Communist Party should not surprise anyone with half a brain and should not be used to question the loyalty of good Australians.”

Dennis Richardson, The Australian

11 November 2019

Australian business broadly wants three things from Australia’s relationship with the PRC. First, it wants to minimise the disruption to trade caused by political tensions. Second, it wants access to the PRC market on a par with the preferential access given to other nations. For example, the PRC does not extend to the Australian pork industry the benefits of the Sanitary/Phytosanitary Standards applied to US pork producers. It should. And third, Australian business wants a bilateral relationship in which Australia has access and influence in Beijing

Where are the voices of business?

There are three principal Australia-based channels for the voice of business on the country’s relationship with the PRC: the Australia China Business Council (ACBC), the Business Council of Australia (BCA) and the Australia-China CEO Roundtable. Each has its shortcomings.

The ACBC has a proud history of support for the bilateral business relationship and is working to further extend its reach and influence into Australian boardrooms. But, membership of the ACBC is largely confined to SMEs. Its influence on federal policymakers and its voice in the media have been muted in recent years. Despite having ASX listed corporate sponsors, the ACBC lacks a sufficient number of senior business leaders. Active participation by influential CEOs is limited, which is in stark contrast to almost every other major bilateral business council.

In contrast to the SME focus of the ACBC, the BCA includes leading ASX companies – many with significant interests in the PRC. However, the BCA’s China Leadership Group is rarely outspoken and chooses to exercise influence behind closed doors. It is largely absent from the public debate and is not intended as a representative body speaking on behalf of a broader business constituency.

The Australia-China CEO Roundtable was established in 2007 and is the centrepiece for business-to-business exchanges with the PRC. But since it only convenes in the margins of meetings between senior leaders, the most recent meeting was held during the 2017 visit of PRC Premier Li Keqiang. That represents three lost years in which Australian business leaders have not had the opportunity to cultivate the business-to-business and personal relationships that could prove valuable to Australia. The absence of these relationships is keenly felt during times of political tension.

This is a sorry state of affairs. It stands in dismal contrast to the annual exchanges fostered by others including the Australia Japan Business Co-operation Committee, the European Australian Business Council and the Australian American Leadership Dialogue.

A new or revitalised platform for business-to-business engagement should be established. This would mark an important step toward restoring business influence into management of the PRC relationship.

An effective platform for dialogue will not just be good for business: Australia needs open channels for frank and, on occasion, discreet discussion with PRC counterparts. CPC leaders may well choose to ignore the message, but there is nevertheless value in alerting Beijing to the adverse impact of the PRC’s behaviour on its global reputation. Business leaders can offer a unique perspective on how Beijing’s coercive trade measures and heavy-handed diplomacy erode confidence in the PRC as a trade and investment partner. At a time when diplomatic channels seem closed, an effective business-to-business dialogue assumes added importance.

A more assertive and effective voice for business will rely on closer collaboration between the BCA, the ACBC and the Australian Chambers of Commerce in the PRC. A business lobby that speaks with a single, authoritative voice will have greater impact than the current patchwork of China-focused business organisations. Australia’s PRC-specific business expertise needs to be concentrated, not dissipated between separate groups with shared interests.

Encouraging business to speak up

The change in behaviour of the PRC is a key factor in the waning of business influence. It has hardened attitudes in Canberra and strengthened the hand of those who regard the PRC as a strategic competitor that threatens Australia’s national security.

Few business leaders are willing to make the case for balancing security interests with commercial interests for fear of being labelled an apologist for the PRC government. Critics are quick to conflate calls for engagement with acts of appeasement. It is not in Australia’s national interest for this toxic climate to continue.

Keeping a low profile made sense in the good times when business ties remained strong and were possibly given greater emphasis than other aspects of the overall relationship. But the good times have passed and laying low is no longer an option for business leaders. COVID-19 has triggered a global recession and the impact of strained diplomatic ties has well and truly spilled over into the trade and investment relationship.

A more assertive voice for business must also be a credible voice. While advocating for sensible engagement, it is important that business leaders acknowledge the legitimate concerns of those who view elements of Beijing’s behaviour as a threat to Australia’s national security. They should support the Australian government’s decision to call out egregious actions such as cyber-espionage, harassment of the Chinese diaspora and meddling in domestic affairs.

Increasing the influence of Australian business in Canberra and Beijing will require the engagement of more senior business leaders who have progressed beyond a strictly buyer/seller relationship with business partners in the PRC. Too few Australians have succeeded in using formal business partnerships as a platform for developing the genuine personal relationships that could be called upon in times of crisis. The PRC’s language and cultural barriers are significant, but they are not insurmountable.

Building deeper personal relationships with counterparts in the PRC requires Australian business to move beyond a fly-in fly-out, transactional approach to business. It demands patience, perseverance and opportunities for genuine dialogue that encourage more than a perfunctory recitation of well-worn talking points.

Recommendations

- Australian business leaders should exercise their right to highlight the importance of the PRC to Australia’s national well-being, and be encouraged to do so without their character or loyalty being impugned.

- The Australian business community should establish a China business lobby of 4–6 business leaders coordinated by the head of the BCA’s China Leadership Group and the ACBC National President. The China business lobby requires stronger collaboration between the BCA and the ACBC and should exercise high-level influence in both Beijing and Canberra

- The Australian government should establish a China Advisory Council, independent of the National Foundation for Australia-China Relations. The Council would support policy by drawing on the collective PRC expertise of business, security agencies, academia and the Australian Public Service. It should report to the Prime Minister through the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Australian business should be proactive in pressing Beijing for an improved trade and investment relationship. This requires stronger collaboration between the BCA, the ACBC and the Australian Chambers of Commerce in the PRC.

- The BCA and the ACBC should work with PRC counterparts to establish a new or revitalised Australia-China CEO Roundtable that meets annually, both independently and in parallel with senior leader visits. Participation in the CEO Roundtable should require a minimum three-year commitment.

Author

Michael Clifton is CEO at China Matters. He spent 20 years with the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, including six years as head of its network in China. Michael has had assignments in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Osaka, and served as an advisor to the Minister of Trade, and Chief of Staff to a senior Cabinet Minister. He is President of the NSW branch of the Australia-China Business Council.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion on how Australian business should address its waning influence on Australia-PRC relations. Our goal is to influence government and relevant business, educational and nongovernmental sectors on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to seven anonymous reviewers who received a blinded draft text and provided comments. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected]