STANCE #16 – APRIL EDITION

By Bryce Morton

Across the world, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its internationally mobile students are changing the face of higher education. So much more than simply ‘fee paying students’, this cohort has laid the foundation for substantial relationships between PRC universities and their international counterparts, increased opportunities within the PRC for students and businesses of the host country, and have been a boon for local business.

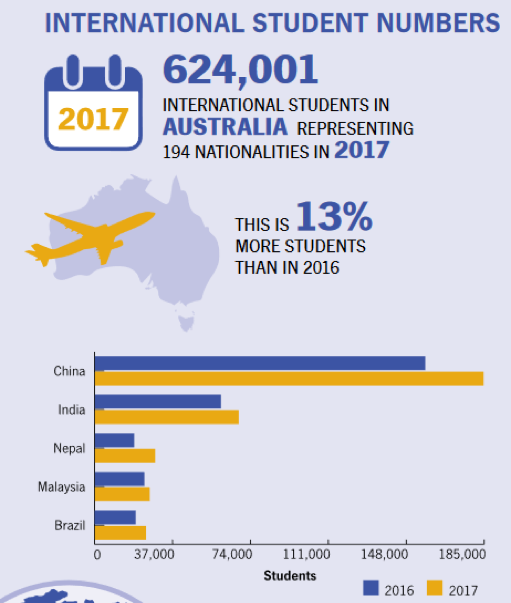

Source – Australian Dept of Education and Training

Yet with this growth comes increased public attention. As such, Australia must work to broaden our public conversation on this topic, or risk damaging one of our largest exports. This YP stance will focus on two key areas to address in this regard.

Firstly, there is a need to untangle any discussion regarding international students from the broader discussions on higher education in Australia, as mischaracterising PRC international students as potential threats harms students, the industry, and distracts from efforts by the Department of Home Affairs to manage legitimate risks when they do appear.

For example, arguments around uncertainty in university funding, concerns about education quality and employability, performance of the vocational education sector, use of tax-payer dollars, and the ‘place/role’ of universities in society are all vital for public input into higher education.

Yet, when considering how international students influence these issues, it’s important not to conflate two separate issues. University funding debates began long before the recent discussion over reliance on international student fees. From the Whitlam Government’s abolition of fees in 1974, to the proposed deregulation of university fees in 2016, universities have always adapted to changing financial contexts.

Another example of muddled debate regards questions on the security of intellectual property, academic integrity, and the influence of foreign governments. These are all serious and legitimate concerns, though are not new challenges facing Australia or its institutions, nor exclusive to Australia’s relationship with the PRC.

It is key to note that the higher education sector relies on the Department of Home Affairs, specifically DIBP and ASIO, to lead risk-management via the granting of visas to come to Australia. While PRC international students receive the most media attention, they constitute only about one-third of Australia’s overall international student engagement. A spokesperson from the Department of Home Affairs has actively spoken about visa requirements, noting that they “are not new and they are not specific to Chinese nationals; they apply to all visa applicants irrespective of their country of origin.”

Second, we must re-evaluate our discourse on international student themselves.

Attention grabbing headlines of student anger over disputed borders, issues with distinction between PRC, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, or self-censorship by PRC students, all cast a negative light on these students.

To completely dismiss these issues would be unwise, particularly given the recent measured warning from ASIO. Yet it is equally unwise to believe that every lecture is a battle of Australian values of free-speech and academic integrity versus the official PRC line, or to see the overwhelming majority of Chinese students in Australia as anything other than normal students.

While some universities may have handled the public relations aspects of these specific situations poorly, we can assume that this isn’t the first time these issues have been discussed in the classroom, and therefore successfully discussed and managed.

Yet we only see sensationalist reporting of isolated incidents which fosters a damaging view of PRC students. The majority of international students seek what their Australian classmates do – to further their education, increase their job prospects, and take a major step into adulthood. To characterise the majority as anything else risks further alienating a group of students who, like all international students, should be welcomed and guided through the expectations and standards of Australian academic (and social) openness and integrity.

To address these two issues, the following actions should be considered by stakeholders within the debate:

- Universities Australia, a non-partisan body representing Australian universities, should step-up its efforts to confront the misrepresentation of some media reports by presenting clear and community-focused statements that help the public understand international and domestic distinctions within the debate; and

- The Department of Education and Training, in consultation with Australian Universities and Colleges, needs to expand the Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) Act and the National Code of Practice for Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students (National Code) to mandate that Australian higher education institutions provide clearly defined and sustained cultural support and engagement programs for international students.

- The Australian government needs to empower the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) to appropriately enforce these changes.

Bryce Morton works at an Australian university and has a keen interest in the international education industry in Australia.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not represent the views of China Matters.

(Photo: Pixabay)