Source: Photo by M.Mono on Pexel

What should Australia do about…

a PRC economic hard landing?

By Jeremy Thorpe

As the economy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has grown it has matured from an overwhelming reliance on investment and exports to one in which a wealthier population has the capacity to consume more than previously.

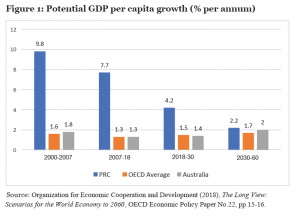

With this maturation, the PRC’s economic growth is slowing to reflect a similar consumption-led economic profile to that seen in advanced economies. This shift is evident in the OECD’s long-term forecasts of GDP growth per capita.

Many commentators are concerned that a shock will disrupt the PRC’s steady path of slowing economic growth to the degree that the PRC experiences a ‘hard landing’.

This matters to Australia because the PRC is the country’s largest trading partner, accounting for nearly a third of all exports. While Australia has benefitted from the growth of the PRC economy, it also leaves us relatively more vulnerable in the event of a downturn.1

Thus, Australia will not be able to avoid economic disruption in the event of a PRC hard landing, although the likely devaluation of the AUD will lessen the immediate shock. In the meantime, maximising overseas market opportunities for Australian businesses is an approach that provides some longer term insurance for the Australian economy.

What might a hard landing look like?

The term hard landing lacks a precise definition. However, analysis of potential scenarios for a hard landing tend to assume a one-off immediate decline in GDP growth of three to five percentage points (from the current annual growth rate of about 6 per cent).

The cause of such a hard landing could come from a range of sources, including:

- external sources, such as:

- a further escalation of the ongoing trade war with the United States. The immediate disruption caused by declining demand for PRC exports will be compounded as corporates re-direct global supply chains away from the PRC so that its capacity to export reduces;

- a US recession, which is now seen by many as a real possibility, would have a negative effect on PRC exports;

- internal sources, such as:

- a debt meltdown in the shadow or formal banking systems. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has noted that ‘perhaps the single biggest risk to the Chinese economy … lies in the financial sector and the big run-up in debt there over the past decade’;2

- a property market correction;

- political disruption (potentially building on the pro-democracy unrest seen in Hong Kong).

As the RBA notes, ‘While there is a broad range of potential triggers for a more severe slowdown in economic growth in China, in recent years authorities have proved capable of responding to individual episodes that posed systemic risk.’3

The likelihood of a hard landing is exacerbated if the triggers are released simultaneously.

Internal and external risks are already aligning, with the trade war slowing PRC economic growth and putting pressure on smaller PRC banks’ loan portfolios. Baoshang Bank was the first PRC bank to fail in 20 years and two others also required government help.

The impact of a PRC economic downturn will depend on the severity and the duration of a hard landing. However, the policy response in Australia and the ability of our businesses to adjust will shape the nature and magnitude of the effect on Australia. The potential scope of outcomes is reflected in the range of results associated with a hard landing predicted by commentators, varying from:

- recession inducing:

- Deloitte modelled the impact of a PRC hard landing in which PRC growth fell from 6.5 per cent to less than 3 per cent. The cost to Australia’s national income was 7 per cent ($140 billion) and 550,000 job losses;4

- to more benign:

- the Asian Development Bank published research that estimated a one percentage point drop in the PRC’s growth rate would cause GDP growth in Australia to fall by around 0.05 percentage points;5

- the International Monetary Fund predicts that a four percentage point fall in Chinese growth would take 0.4 percentage points from Australian growth in the short term;6

- RBA staff modelled three hard landing scenarios, noting that ‘We show that a slowdown in PRC economic activity of around 5 per cent could result in a decline in Australian GDP of up to 2½ per cent [after three years], depending on the nature of the scenario.’7

To understand the nature and scale of the likely impacts, and what should be done, this brief investigates the impacts in the short term and over the medium term.

Short-term impacts

A significant drop in PRC growth will have an immediate negative impact on Australia’s exports to the PRC as lower incomes reduce demand for Australian goods and services. Any sharp drop in PRC growth will trigger a fall in the Australian Dollar against the United States Dollar and other major traded currencies because the AUD is seen as a proxy currency for the PRC economy.

For companies with the bulk of their earnings from overseas buyers (e.g. education, tourism, etc.), a fall in the AUD would be a welcome event. Even domestically focused organisations with non-PRC investments will benefit from such a depreciation in the AUD.

As the tradeable goods sector makes up about 40 per cent of the Consumer Price Index basket, such a depreciation of the AUD would increase consumer prices (i.e. inflation) in Australia. This would ordinarily be seen as a bad outcome, but with inflation below the RBA target range of 2-3 per cent, increased inflationary pressure will be unlikely to have a major impact on the Australian economy.

Australian state and federal governments will lose revenue from a PRC hard landing. Most directly will be the loss of mining-related tax revenues. At risk are:

- state and territory royalties — in 2019-20 I expect mining companies to pay $14.8 billion in royalties to state and territory governments.8 In practice the bulk of royalties are captured by Western Australia ($6.4 billion) and Queensland ($5.6 billion)

- Commonwealth company taxes — in 2019-20 I expect mining companies to pay the Commonwealth in the order of $31.1 billion in company tax.9 For context, in 2019-20 the Australian Government expects to spend the same amount ($31.5 billion) on school education and higher education.10

Reduced demand for natural resources in the PRC will cascade into lower commodity prices more generally and so undermine projections of the Commonwealth heading back into a Budget surplus (projected to be $7.1 billion in 2019-20).11

Any significant fall in commodity prices off the back of the PRC’s accelerated slowdown would likely result in mine closures or mothballings, with consequent job losses in pockets of regional Australia and lower royalties.

Hence, in addition to the revenue shock for Australian governments there would also be additional

budgetary costs from a PRC slowdown. These would take the form of:

- additional stimulus provided (whether in the form of direct payments to households, accelerated infrastructure spending, etc.)

- increased welfare payments as unemployment increases;

- increased welfare and other payments where they are linked to CPI changes;

- higher debt servicing payments as budgets move into deficit.

Additionally, access to capital for both public and private organisations will become more challenging in this environment as we can expect to see:

- rising bank funding costs (as Australia’s risk premia rises);

- reduced foreign investment. At most risk is PRC investment. The PRC is Australia’s fifth largest direct investor. This will in turn result in tighter liquidity.

Limiting the downside of a hard landing, but also limiting the benefits to Australia during the PRC’s rise, is that Australia has only a limited exposure to the PRC through investments into the PRC. The PRC hosts just 3 per cent of Australian investment abroad (compared to 29 per cent in the US) and so the direct downside is limited from an investment perspective.

Medium term impacts

In the medium term we can expect to see some of the negative first-round impacts of a hard landing ameliorated.

- Impacts of the AUD’s depreciation

The depreciation of the AUD will increase the competitiveness of:

- all Australian exporters, acknowledging however that the PRC downturn will drag down global growth

- domestic firms competing with international rivals in Australia. For example, as long as the PRC Government does not seek to reign in its students studying abroad, we may see Australia attract a new cohort of price-sensitive PRC students shifting from higher cost markets coming to Australia as the cost of education falls.

The risk for the Australian economy is that the PRC currency (CNY) will likely decline, which will partially offset the decline in the AUD/USD rate. Hence, while the depreciation of the AUD is an important shock absorber, it may be less responsive in the case of a PRC hard landing.

2. Impact of a global slowdown

As the largest global trader, the PRC’s economic health affects the global economy as a whole. Thus, we can expect that other countries will also take a hit from a PRC hard landing, leading to lower global economic growth generally. This will depress growth opportunities as companies look to diversify away from the PRC.

3. Potential PRC responses

History (e.g. during the GFC) suggests that we could also expect the PRC to respond to any major downturn in growth with stimulatory measures designed to boost growth. Such measures have tended to involve major construction initiatives, with consequent increases in demand for Australian natural resources (iron ore and coal predominantly). This has the potential to be a major offset against an initial downturn in demand.

However, it is also possible the PRC Government’s concerns about its current account position result in more active measures to control outbound:

- tourism spending – outbound tourism is a material negative impact in terms of the PRC’s current account balance;

- international student flows – there is a medium/long term ambition to lift standards domestically and thus moderate flows

Both of these possible responses would be significant shocks to major Australian service export industries.

Additionally, we can reasonably expect to see:

- to divert attention from the country’s economic challenges. This may further increase the global risk profile and limit trade;

- a reduction in state-directed investment as a form of diplomatic engagement.

Policy recommendations

Pre-emptively, the Australian Government should:

- continue prosecuting broad free trade agreements (FTAs) to enhance flexibility for exporters in the event of a PRC hard landing. In the short-term priority should be given to concluding:

- the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (ASEAN plus Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, the PRC and South Korea). The 16 participating countries account for over 60 per cent of Australia’s two-way trade, 17 per cent of two-way investment, and over 65 per cent of Australia’s goods and services exports;

- the Australia-European Union FTA will open up a market for Australian goods and services of half a billion people and a GDP of US$17.3 trillion;

- invest in supporting Australian firms to enter/grow in a broader range of markets (e.g. India). Such an approach needs to acknowledge, however, that companies follow demand and the PRC will remain Australia’s largest export market;

- ensure that the risks/costs of a PRC hard landing are adequately captured in bank provisions so that any significant downturn can be accommodated/managed by the Australian banks.

Hence, in the event of a hard landing the Australian Government should:

- resist the temptation to ‘protect’ or ‘support’ the AUD; the AUD’s flexibility is a key mechanism for managing the shock of a PRC hard landing;

- be prepared to sacrifice projections of the Budget returning to surplus given likely tax revenue shocks and the need to increase spending to stimulate the economy;

- be nimble diplomatically to respond to changing dynamics in countries of diplomatic interest if the PRC pulls back state-directed investment;

- assist negatively affected agricultural producing and resource-intensive communities to adjust to a PRC slowdown.

Author

Jeremy Thorpe is PwC’s Chief Economist and is a Partner in PwC’s national Economics & Policy team. He provides macroeconomic and associated policy advice for both corporates and governments. He has provided advice to the Australian Government on the costs, benefits and utilisation of free trade agreements and modelled the economic impact of the PRC halting foreign students coming to Australia.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion of the PRC economy and its implications for Australia. Our goal is to influence government and relevant business, educational and non-governmental sectors on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to six anonymous reviewers who received a blinded draft text and provided comments. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected].

Notes

- Yvan Guillemette & David Turner, ‘The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060’, OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 22, 12 July 2018, pp. 15-16.

- Philip Lowe, ‘Australia’s Deepening Economic Relationship with China: Opportunities and Risks’ presented at the Australia-China Relations Institute, Sydney, 23 May 2018.

- Rochelle Guttmann, Kate Hickie, Peter Rickards & Ivan Roberts, ‘Spillovers to Australia from the Chinese Economy’, RBA Bulletin, June 2019, pp. 87-110.

- Deloitte, ‘Building the Lucky Country #6 – What’s over the horizon? Recognising opportunity in uncertainty’, 2017.

- Tomoo Inoue, Demet Kaya & Hitoshi Ohshige, ‘Estimating the Impact of Slower People’s Republic of China Growth on the Asia and the Pacific region: a Global Vector Autoregression Model Approach’, in Justin Yifu Lin, Peter J. Morgan & Guanghua Wan (eds), Slowdown in the People’s Republic of China: Structural Factors and the Implications for Asia, Asia Development Bank, March 2018, pp. 357-373.

- Philippe D Karam & Dirk V Muir, ‘Australia’s Linkages with China: Prospects and ramifications of China’s economic transition’, IMF Working Paper WP/18/119, 22 May 2018.

- Rochelle Guttmann, Kate Hickie, Peter Rickards & Ivan Roberts (2019), ‘Spillovers to Australia from the Chinese Economy’, RBA Bulletin, June, pp. 87-110.

- Analysis of State and Territory 2019-20 Budget papers.

- Deloitte Access Economics, ‘Estimates of royalties and company tax accrued in 2017-18, Minerals Council of Australia’, 26 March 2019; Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019), 5676.0 Business Indicators, Australia, Mar 2019, 3 June 2019; Australian Government, ‘Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1 2019-20’, April 2019.

- Australian Government, ‘Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1 2019-20’, April 2019, pp. 5-17.

- Secretary to the Treasury & Secretary of the Department of Finance, ‘Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2019’, April 2019, p. 1.