PRC’s approach to Indonesia:

Competing for regional influence

by Yun Jiang

Executive Summary

- In competition for regional influence with the US, the PRC pursues its interests with Indonesia by appealing to Jakarta’s domestic priorities and generally choosing to use incentives over coercion.

- The PRC is not worried about Indonesia’s refusal to pick a side between Beijing and Washington or Jakarta’s lack of trust in Beijing because it is preferable to Indonesia aligning with the US.

- Despite being the cornerstone of the bilateral relationship, trade and investment links have led to anti-PRC sentiment in Indonesia. Yet, the PRC’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims or activities in the South China Sea, have not caused significant damage to the relationship.

- PRC domestic media downplays anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia to avoid provoking nationalist retaliation. A stable bilateral relationship is more important to the PRC government than the Chinese diaspora in Indonesia.

- Australia should work together with the PRC and Indonesia on global governance issues such as climate change and digital standards.

Introduction

Geopolitical competition between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States is intensifying in the Indo-Pacific region, where both countries are stepping up efforts to court others into their sphere of influence. As the PRC anticipates a new Cold War with the West, it seeks closer cooperation with countries outside Europe and the Anglosphere. Indonesia is a prized partner.1

In this report, I examine how the PRC pursues its geopolitical interests with Indonesia by appealing to Jakarta’s domestic priorities of economic development and national unity. I show how, contrary to the mainstream narrative in Australia, the PRC prefers incentive-based tools of engagement over coercive methods, because Indonesia responds well to Beijing’s overtures and has been reciprocally pragmatic. This explains why, according to the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index, the PRC is more influential than the US in Indonesia.2

Indonesia is of significant strategic importance to Australia. It is the first international destination for many new prime ministers. A stable and secure Indonesia that is not strategically aligned with the PRC is important to Australia’s security interests, particularly given rising concern in Canberra regarding a potential conflict between the US and the PRC, which may lead to Australian or PRC military operations in Indonesian territorial waters.3

I argue, however, that Canberra should not be unduly anxious about the warming relationship between the PRC and Indonesia under Presidents Xi Jinping and Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi). The PRC is unlikely to force Indonesia to choose between Beijing and Washington. It may not like the answer, and any attempt at coercion would likely backfire. Indonesia does not want to choose either, electing instead to continue hedging between the two great powers.

The report begins by outlining a history of the PRC’s policies and approaches towards Indonesia, and then it examines current opportunities and tensions in the bilateral relationship from the PRC’s perspective. Finally, I assess the implications for Australia and offer policy recommendations.

The PRC’s evolving approach to Indonesia

Over the last decade, the PRC has ramped up engagement with Indonesia, particularly under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This reflects Beijing’s recognition of the increasing geoeconomic importance of countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Indonesia’s expanding influence in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia has become a focal point for PRC–US geopolitical competition, especially following the Obama administration’s so-called “pivot” to Asia in 2011. This year, Indonesia assumed the ASEAN chair. Indonesia is seen by the PRC as the “bellwether” of ASEAN and as a “natural leader.”4

By having a closer relationship with Indonesia, the PRC hopes it can also cultivate better ties with other ASEAN countries.5

ASEAN has been the PRC’s largest trading partner since 2020, while the PRC has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner for the last 13 years. Between 2010 and 2022, two-way trade quadrupled from US$235.5 billion to US$975 billion per annum.6

The ASEAN economies are likely to become increasingly important to the PRC. An analyst from ANBOUND, a PRC-based think tank, says: “US containment of China’s technology and economy will become the norm […] China needs to locate new external growth space [and] Indonesia is likely to become an important partner of China in ASEAN in the future.”7

Apart from ASEAN, the PRC also sees Indonesia as being influential in global affairs due to its membership of the G20, its identity as a Muslim-majority country, its growing economy, and its geographical location as a maritime country close to many international shipping lanes and strategic passages.8

The PRC believes its bilateral relationship with Indonesia is currently stable because there is no clash of fundamental interests.[9] In 2022, in a meeting with Jokowi, Xi described the two countries as “having similar stages of development, joint common interests, shared ideas and intertwined destinies.”10

A turbulent history

The PRC and Indonesia established diplomatic relations in 1950. Indonesia then hosted the Bandung Conference for the Non-Aligned Movement in 1955, which paved the way for positive relations.

However, the ascendency of the avowedly anti-Communist General Suharto dealt a blow to the relationship. Indonesia suspended diplomatic relations in 1967, blaming the PRC for a failed coup. By then, with the Cultural Revolution in full swing, Beijing’s attention had turned inward.

Relations began to thaw in 1985 with a visit to Indonesia by the PRC foreign minister for the 30th anniversary of the Bandung Conference. Gradually, direct trade restarted. Diplomatic relations were officially restored in 1990, and the PRC foreign minister reassured Jakarta that Beijing would not interfere in Indonesia’s domestic affairs.11

These improvements in relations accelerated after Suharto stepped down in 1998. Around that time, three developments brought the two countries closer.

First, the PRC’s decision to not devalue its currency in the aftermath of the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis greatly enhanced its reputation in the region. The Western-led International Monetary Fund was viewed less favourably.

The crisis strengthened financial and economic links between the PRC and Southeast Asia. It led to stronger regional cooperation and laid the groundwork for the rising importance of economics in the PRC’s approach to Southeast Asia.

The second development in relations was the PRC’s subdued response to the 1998 Indonesian anti-Chinese riots. Indonesia has always regarded PRC statements on the protection of Chinese Indonesians as interference in its domestic politics.

By the 1990s, the domestic priorities of the PRC had shifted. The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, including non-interference in internal affairs, began guiding Beijing’s foreign policy towards Indonesia.12 Developing better relations with countries in the region became more important than supporting foreign communist movements or managing the Chinese diaspora.

The PRC curtailed its public statements on the riots.13 Over time, Beijing has avoided commenting on any anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia.

The third development in relations happened during the 1999 East Timorese independence referendum. The US imposed an arms embargo on Indonesia over human rights concerns. Trust in the US subsequently diminished in Indonesia, especially in the military.14 The PRC’s approach to the crisis was more pragmatic, prioritising the bilateral relationship. Beijing supported a United Nations intervention only after Indonesia had already agreed to it.15

Indonesia learnt that the US was not a benign provider of security.16 From the PRC’s perspective, Indonesia became more susceptible to a charm offensive, which began in the 2000s, to prevent countries from becoming too close to the US.17

Trade and investment ties

Since the launch of the BRI in 2013, trade and investment has become the cornerstone of Indonesia–PRC bilateral cooperation. The PRC sees trade and investment ties as “win-win” and one area where it has a visible advantage over the US.

The PRC has been Indonesia’s largest trading partner since 2005. Economic links between the two countries are likely to grow under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free-trade agreement by members’ GDP, covering 15 countries in the Indo-Pacific region, in force from 2022.

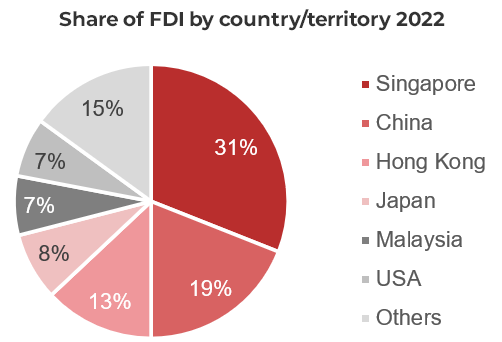

Since 2017, the PRC has also been Indonesia’s second-largest source of foreign investment. Indonesian officials have said that, compared to the US, PRC companies “never, ever dictate.”18 Beijing’s favourable attitude and scale of investment are mentioned by PRC observers as reasons why Indonesia resists US pressure to pick a side.19

Indonesia is the PRC’s second-largest investment destination in ASEAN.20 Xi launched the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, a key pillar of the BRI, in Jakarta in October 2013.

Source: ARC Group

After the election of Jokowi in 2014, the PRC promoted the BRI as complementary to his “Global Maritime Fulcrum” strategy. Frequent references are made to the two visions in joint leaders’ declarations.21 With Jokowi due to step down next year, this is unlikely to be carried over to the next administration.22

The landmark project connecting the BRI and the Global Maritime Fulcrum strategy is the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed railway. This is scheduled to commence operation this year, after extensive delays and problems with, for example, budget, land acquisition, and environmental concerns. Other key BRI projects include industrial parks under the “Two Countries, Twin Parks” banner.

Another important aspect of the BRI in Indonesia is cooperation in the digital economy. PRC technology companies are at the forefront of driving this Digital Silk Road. Huawei is installing telecommunication infrastructure in Indonesia, as well as providing training to Indonesian officials, professionals, and university students.23

For Indonesia, this digital training fills a much-needed capacity gap. For Beijing, it enmeshes Indonesia in the PRC’s digital ecosystem, making it difficult for Indonesia to decouple from PRC technology if pressured by the US to do so.

Opportunities and tensions in the bilateral relationship

The current PRC–Indonesia bilateral relationship is generally positive. Issues that might generate tension, such as the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea or the PRC’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, have not caused significant damage to the relationship. However, ironically, aspects of the relationship that the PRC sees as providing ballast, such as investment, have sometimes led to anti-PRC sentiment in Indonesia.

Public opinion in Indonesia has turned increasingly negative against the PRC, according to numerous recent surveys.24 Negative sentiments have been downplayed by PRC domestic media. Beijing is confident that the relationship has strong foundations and that they can work with whomever is in power following the next Indonesian election.25

Trade and investment

The PRC believes that economic cooperation is the main driver of the bilateral relationship.26 Beijing promotes itself as a partner for development.

In talks with Southeast Asian governments, Beijing often highlights its free-trade credentials. The ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) is ASEAN’s oldest free-trade agreement among its dialogue partners.27 Negotiations on revisions (or “upgrades”) of ACFTA occur over time. More recently, the PRC and ASEAN countries have become parties to the RCEP.

PRC officials frequently disavow “unilateralism, protectionism and hegemonism” when interacting with Indonesian officials.28 The PRC intends to provide a contrast to the security-focused approach of the US in the region. Until recently, the US has not been actively involved in trade negotiations in the Indo-Pacific region, since withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017.

Washington’s economic initiatives have not had as much impact in the region. President Joe Biden’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, launched last year, crucially does not include market access.29 One observer was quoted saying: “The joke here is the Chinese have worked their way through a five-course meal and are onto dessert, while the West are still looking outside at the menu.”30

Even though economic cooperation is a positive aspect of the bilateral relationship, it has also proven to be a source of domestic tension in Indonesia, contributing to a negative view of the PRC. A poll conducted in Indonesia in 2021 by the Lowy Institute found that less than half of Indonesians think the PRC’s economic growth has been good for Indonesia. Another survey conducted by the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in 2022 showed that more than 40 per cent of Indonesians are worried about the BRI.31

Critiques of trade with the PRC focus on the influx of cheap products made in the PRC, which threatens domestic Indonesian industries and employment. Criticism of PRC investment centres on the use of PRC migrant workers over domestic Indonesian workers.32 PRC companies attempt to curb such criticism by making donations and helping local organisations, schools, and mosques, among other corporate social responsibility initiatives.33

Despite domestic concerns in Indonesia, the PRC still sees trade and investment as the most promising and positive aspect of bilateral relations. Beijing is confident this will bring the two countries closer politically in the long run.

Anti-Chinese sentiment

Resentment in Indonesia towards the PRC and PRC migrant workers is conflated with general distrust of Chinese Indonesians. According to a 2022 survey, more than 40 per cent of Indonesians think that Chinese descendants are loyal to the PRC.34

This emotionally charged issue was politicised during the 2019 Indonesian election, with disinformation circulating, claiming that Indonesia was facing an influx of millions of Chinese workers.35 This follows the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, in which the Chinese Indonesian incumbent governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as Ahok) was accused of blasphemy by his opponents and subsequently imprisoned.

Public response in the PRC has mostly been muted. Beijing and state media have refrained from commenting or reporting on anti-PRC or anti-Chinese sentiment during Indonesian elections. This is a deliberate strategy to prevent an outpouring of nationalism from derailing the bilateral relationship. In addition, it also makes the PRC policy towards Indonesia appear more effective to the domestic audience.

Beijing believes anti-Chinese sentiment is drummed up by political opposition in Indonesia for political gain, and remains largely unconcerned by it.

When Prabowo Subianto was running in the 2018 presidential election, he attacked Jokowi as being a communist and ethnically Chinese. PRC analysts portrayed this as a struggle between progressivism and conservatism rather than as anti-Chinese sentiment.

Prabowo appeared to become more conciliatory towards Beijing after he joined the Jokowi administration as defence minister. His speech at the 2022 ShangriLa Dialogue was publicised in the PRC, quoting him saying: “We are convinced that the leaders of China will stand up to their responsibility with wisdom and benevolence.”36

The Natuna Islands

The way the PRC approaches the South China Sea issue with Indonesia is different from the way it approaches disputes with other Southeast Asian countries. This is because Indonesia asserts that it is not a claimant to the South China Sea. The two countries agree that Indonesia has sovereignty over the Natuna Regency.

However, the PRC’s nine-dash line overlaps the exclusive economic zone of Natuna, and PRC Coast Guard and fishing vessels have been operating in that maritime area without permission from the Indonesian Government. The PRC says these maritime areas are part of Chinese “traditional fishing grounds.”37

For the PRC, the nine-dash line is the foundation of Beijing’s wider claims in the South China Sea. Giving in on this issue would signal Beijing’s lack of resolve with regard to other claims. For Indonesia, its territorial integrity is sacrosanct.

While Indonesia has vocally protested incursions by PRC vessels, Beijing is largely satisfied with Jakarta’s handling of these incidents. The two countries appear to have reached a tacit understanding by which both sides stand firm publicly and conduct low-key diplomatic negotiations.38

In 2020, after PRC fishing vessels were found in Natuna waters, Jokowi visited Natuna to show his resolve on territorial integrity. The Indonesian foreign minister summoned the PRC ambassador and lodged an official protest, while the foreign ministry cited the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling on the South China Sea.

However, at the same time, the Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investments was careful to link the importance of Indonesia’s exclusive economic zones to the economy, not to sovereignty.39 He expressed appreciation for the PRC’s efforts in reducing the number of fishing vessels in the area. Defence Minister Prabowo also downplayed the dispute, saying: “We can resolve this amicably. After all, China is a friendly nation.”40

It has been Beijing’s strong preference not to internationalise the dispute. Attempting to resolve issues bilaterally gives the PRC more flexibility to offer inducements in exchange for a more muted response from Indonesia.

Nevertheless, as Indonesia starts to develop its offshore gas project near the Natuna Islands, the PRC is likely to send its Coast Guard vessels to the area more frequently, as it has done with gas projects in Malaysia and Vietnam. This may cause greater friction in the bilateral relationship in the future.

Xinjiang

Indonesia is a Muslim-majority country. However, despite regular rallies in Indonesia against the PRC’s treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the government has not been vocal in criticising the PRC, and President Jokowi has dismissed questions on this issue. This is due to several considerations.

First, the two governments are aligned in their opposition to secession. The PRC knows Indonesia would not support any push towards independence or autonomy for the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, because Indonesia does not want other countries to support the secession of West Papua. Similarly, the PRC understands that Indonesia is reluctant to raise human rights concerns in Xinjiang because doing so would draw attention to Indonesia’s own human rights record in West Papua.41 Both the PRC and Indonesia consider human rights criticisms as interference in their domestic affairs. The way in which the PRC frames its actions in Xinjiang as “counterterrorism” also helps Beijing garner Indonesian support.

Second, since 2016, the PRC has been active in faith diplomacy towards Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, the two largest Islamic faith groups in Indonesia.42 The PRC regularly invites clerics and scholars to attend exchanges and dialogues, and it donates money to these organisations for charitable causes, such as orphanages and schools.43

Third, domestic Indonesian politics has subdued public criticisms of the PRC’s actions in Xinjiang. The groups in Indonesia that are most vocal on Xinjiang also tend to be anti-government. For example, the Islamic Defenders Front protested the treatment of Uyghurs outside the PRC embassy in 2018 and 2019.44 The group also made frequent racist remarks against Chinese Indonesians and intimidated religious minorities, and was subsequently banned by the Indonesian Government in 2020.45

Strategic alignment

Beijing is appreciative of Indonesia’s steadfast refusal to pick a side between the PRC and the US. Analysts in the PRC praise Indonesia’s resistance to US pressure. Guancha analyst Xiong Chaoran observed: “Despite the US continuously ‘fanning the fire’ in the Asia-Pacific region, and some people deliberately provoking tensions, Southeast Asian countries, led by the largest country Indonesia, have already stated that they will not take sides.”46 Some analysts have contrasted this with Australia joining the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and the trilateral security pact AUKUS, which they perceive as a choice of the US over the PRC.47

While Beijing is confident that the trajectory of positive PRC–Indonesia bilateral relations will continue, the two countries are unlikely to develop a strategic alignment.

This is because there is still significant distrust of the PRC among both Indonesia’s elites and the wider population. For Indonesia’s elites, PRC militarisation in the South China Sea and fear of PRC influence over Chinese Indonesians remain obstacles.48 Among the wider population, negative perceptions and distrust stem from anti-Communist sentiment, as well as grievances at the economic dominance of the PRC. Nearly half of Indonesians see the PRC as a threat in the next decade.49

Beijing is not overly worried about Indonesia’s lack of trust in the PRC, because it understands that Indonesia does not fully trust the US either. The PRC prefers countries to take a non-aligned or hedging position instead of joining a bandwagon with the US against PRC interests. As countries such as Indonesia seek to cooperate with both the PRC and the US when it suits their interests, the PRC can be more agile in offering more substantial economic opportunities.50

What does this mean for Australia?

Instead of seeing Indonesia as a passive target in a geopolitical tug-of-war between the US and the PRC, Australia should support Indonesia in becoming a regional and global player in its own right, especially as the Indo-Pacific region becomes increasingly multipolar.

Indonesia could soon have substantial international influence of its own.51 This is largely due to anticipated future economic growth in the region. Goldman Sachs has projected that Indonesia will be the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2050.52

This necessitates a re-orientation in how Australia thinks about Indonesia. In particular, Australia needs to accept that Indonesia will play a bigger role in international affairs than Australia, as its economy grows to be one of the biggest in the world.53

It is in Australia’s interest that Indonesia remains stable and secure. A military conflict would devastate growth prospects. The Indonesian Government is gravely worried about an arms race and militarisation in the region. The Indonesian ambassador to Australia has previously raised concerns regarding an arms race in the context of AUKUS.54

The PRC uses a regional arms race as a way to criticise US deployment in the region, including in Australia. For example, in 2022, the PRC foreign ministry spokesperson criticised the US for its deployment of B-52 nuclear-capable bombers in Australia, thereby “seriously undermining regional peace and stability, [which] may trigger an arms race in the region.”55

Unlike Australia, Indonesia has refused to be a military base for any country, including both the PRC and the US.56

Recommendations

To engage more effectively with Indonesia and build a closer relationship, Australia should recognise and work with Indonesia’s domestic and foreign policy interests.

One of Indonesia’s top interests is its economic development and global integration. Australia has been successful in getting the US more engaged militarily in the region, but less successful in doing so economically, due to a powerful protectionist sentiment in the US. As a close ally of the US, Australia should encourage more regional economic engagement from Washington, including through the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity.57

Australia should also explore areas of cooperation with the PRC in Indonesia. This would benefit Indonesia’s economic development while at the same time advancing the Australia–China bilateral relationship. In 2017, Australia signed a memorandum of understanding with the PRC on cooperation in investment and infrastructure in third countries. As the PRC expands investment in clean energy in Indonesia, Australia should consider partnering with Beijing on delivering climate and energy commitments. One example would be helping Indonesia to develop its electric vehicle battery industry.

The three countries should work together on global governance issues such as climate change and digital standards. Australia and Indonesia have a good track record of working together at multilateral forums such as the G20. This not only helps build trust between the three countries, but it can also shape the future of regional and global rules and institutions.

US efforts to technologically decouple from the PRC mean that Indonesia is under pressure from the US to choose US technology in order to continue defence cooperation and ensure interoperability.58 However, PRC technology companies such as Huawei have become an important part of Indonesia’s telecommunication and technology landscape. Australia should consider how to work with Indonesia regardless of what technology it chooses. This can include advocating for technologies that can work with both PRC and US systems.

Finally, Australia should humbly learn from Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries.59 Indonesia has been managing ambiguity and complexity in geopolitics for far longer than Australia.

Author

Yun Jiang is the inaugural AIIA China Matters Fellow at the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) and China Matters. She was previously co-founder and editor of the newsletter China Neican, and a managing editor of the China Story blog. She is a former researcher in geoeconomics at the Australian National University and a former policy adviser in the Australian Government.

The Australian Institute of International Affairs and China Matters do not have an institutional view on the subject of this report; the views expressed here are the author’s.

The AIIA China Matters Fellowship is an investment in the next generation of Australian China specialists. The Fellow will publish well-researched and publicly accessible reports on developments in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) which are especially relevant to Australia and add depth and alternative views to the vital debate about Australia’s relationship with the PRC.

Established from 1924 as branches of the Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House) and as a national body in 1933 as the Australian Institute of International Affairs, the AIIA is Australia’s longest established private research institute on international affairs and foreign policy. The institute’s mission is to have Australians know more, understand more, and engage more in international affairs. AIIA branches in every state and territory capital city, as well as a national office based in Canberra, arrange over 150 events per year, and the institute publishes premium publications such as the Australian Journal of International Affairs and Australian Outlook, its online publication.

China Matters is an independent Australian policy institute that strives to advance sound China policy by injecting nuance and realism as well as a diversity of views into debates about the PRC and the Australia-China relationship.

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers who each did a blind review.

Notes

- Yuan Yujing (2022), “The Development Potential of Indonesia and What It Means to China”, ANBOUND.

- Susannah Patton and Jack Sato (2023), “Asia Power Snapshot: China and the United States in Southeast Asia”, Lowy Institute.

- Australia’s Defence Strategic Review (2023) notes that “major power competition in our region has the potential to threaten our interests, including the potential for conflict”.

- 王玥 Wang Yue (2022), 印太语境下澳大利亚与印度尼西亚的海洋安全合作 “Analysis of the Australia-Indonesia maritime security cooperation from the Indo-Pacific perspective”, 印度洋经济体研究 Indian Ocean Economic and Political Review.

- Many analysts in the PRC describe Indonesia as the “bellwether” (领头羊) of ASEAN.

- Hou Yanqi (2023), “China and ASEAN: Cooperating to build an epicentrum of growth”, The Jakarta Post.

- Yuan Yujing (2022), “The Development Potential of Indonesia and What It Means to China”, ANBOUND.

- For how the PRC sees Indonesia’s importance in foreign relations, see, for example, 邹志强 Zou Zhiqiang (2022), G20 峰会背景下中国与印尼的全球经济治理合作 “Global economic cooperation between China and Indonesia in the context of the G20 Summit”, 南亚东南亚研究 South and Southeast Asian Studies.

- 包广将 Bao Guangjiang and 林晓丰 Lin Xiaofeng (2022), 地位焦虑: 印尼应对中美战略竞争的逻辑 “Status anxiety: The logic of Indonesia’s response to China–-US strategic competition”, 南洋问题研究 Southeast Asian Affairs.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2022), 习近平同印度尼西亚总统佐科会谈.

- Michael Williams (1991), “The role of the Indonesian Chinese in shaping modern Indonesian life”, Indonesia, Cornell University Press.

- Although the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence were first articulated in 1954 in relations with India, the PRC only stopped promoting revolutionary ideology in the late 1970s. See Zhou Yi (2020), “Less revolution, more realpolitik: China’s foreign policy in the early and middle 1970s”, The Wilson Center.

- 李启辉 Li Qi-hui and 孙建党 Sun Jian-dang (2021), 印尼对华认知的变化轨迹—基于复交以来印尼主流媒体的实证分析 “Changes in Indonesia’s perception of China since 1990: An analysis of mainstream Indonesia media archives”, 南洋问题研究 Southeast Asian Affairs.

- Evi Fitriani (2021), “Linking the impacts of perception, domestic politics, economic engagements, and the international environment on bilateral relations between Indonesia and China in the onset of the 21st century”, Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies.

- J. Mohan Malik (1999), “Why Beijing is cooperating with the Timor action”, International Herald Tribune.

- Evan Laksmana (2023), “Embracing the different ways Indonesia and Australia view the region”, The Interpreter.

- Lye Liang Fook (2020), “China’s Southeast Asian Charm Offensive: Is it Working?”, Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Sui-Lee Wee, Eric Schmitt, and Jane Perlez (2023), “China and the US are wooing Indonesia, and Beijing has the edge”, New York Times.

- Guancha (2023), 印尼官员:中国人从不向我们发号施令,美国官员倒是经常提苛刻条件.

- According to the PRC Government, the top direct investment destinations in ASEAN are Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

- For example, the 16 November 2022 Joint Statement and the 26 July 2022 Joint Press Statement both mention cooperation between the BRI and the Global Maritime Fulcrum.

- Despite its appearance in joint statements, the Global Maritime Fulcrum has largely disappeared from Indonesia’s domestic messaging since Jokowi’s second term in 2019. See Evan Laksmana (2019), “Indonesia as ‘Global Maritime Fulcrum’: A post-mortem analysis”, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative Update.

- Gatra Priyandita, Dirk van der Kley and Benjamin Herscovitch (2022), “Localization and China’s tech success in Indonesia”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- A survey by the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute conducted in 2022 found more respondents perceive a negative impact from the rise of China than a positive one. This is an opposite response to the same survey question asked in 2017. Similarly, the Lowy Institute Indonesia Poll conducted in 2021 found Indonesians are increasingly sceptical about China, and particularly about Chinese investment, with only 43 per cent of Indonesians believing that China’s growth has been good for Indonesia, compared to 54 per cent in 2011.

- 李启辉Li Qihui and 孙建党Sun Jiandang (2020), 印尼主流社会的中国形象变迁 “The changing image of China in Indonesian mainstream society”, 中国社会科学报 Chinese Social Sciences Today.

- 邹志强 Zou Zhiqiang (2022), G20 峰会背景下中国与印尼的全球经济治理合作 “Global economic cooperation between China and Indonesia in the context of the G20 Summit”, 南亚东南亚研究 South and Southeast Asian Studies.

- ASEAN Secretariat (2022), “ASEAN, China announce ACFTA upgrade”.

- For example, Li Zhanshu in 2022, when speaking to Indonesia’s speaker of the House of Representatives Puan Maharani: http://id.china-embassy.gov.cn/zgyyn/202012/t20201211_2084686.htm.

- Aidan Arasasingham and Emily Benson (2022), “The IPEF gains momentum but lacks market access”, East Asia Forum.

- Emma Connors (2023), “China steps up regional Asian investment to counter US influence”, Australian Financial Review.

- ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (2023), The Indonesian National Survey Project 2022.

- Dewi Fortuna Anwar (2019), “Indonesia–-China Relations: Coming full circle?”, Southeast Asian Affairs.

- Xinhua (2022), “Chinese companies contribute to Indonesia’s economic, social development: report”.

- ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (2023), The Indonesian National Survey Project 2022.

- Rebecca Henschke (2019), “Indonesia 2019 elections: How many Chinese workers are there?”, BBC News.

- Prabowo Subianto (2022), “Second plenary session: managing geopolitical competition in a multipolar region”, 19th Regional Security Summit, The Shangri-La Dialogue.

- Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying (2016), “Remarks on Indonesian Navy Vessels Harassing and Shooting Chinese Fishing Boats and Fishermen”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Yizheng Zou (2023), “China and Indonesia’s responses to maritime disputes in the South China Sea: forming a tacit understanding on security”, Marine Policy.

- Dian Septiari (2020), “Not about sovereignty: Luhut explains Natuna spat with China”, The Jakarta Post.

- Aaron Connelly (2020), “Indonesia and the South China Sea under Jokowi”, Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment 2020.

- Max Walden (2019), “Indonesia’s opposition takes up the Uighur cause”, Foreign Policy.

- Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat (2022), “China’s faith diplomacy towards Muslim bodies in Indonesia: bearing fruit”, Fulcrum.

- Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat (2022), “China’s faith diplomacy towards Muslim bodies in Indonesia: bearing fruit”, Fulcrum.

- Maya Wang and Andreas Harsono (2020), “Indonesia’s silence over Xinjiang”, Human Rights Watch.

- Reuters and Kate Lamb (2020), “Indonesia bans hardline Islamic Defender’s Front group”, Reuters.

- 熊超然Xiong Chaoran (2022), 美军最高将领在印尼渲染“中国威胁论”之际,印尼总统佐科抵达中国访问 “At a time of a high-ranking US military official fuelling the China threat theory, Indonesian President Widodo visits China”, Guancha.

- 齐倩Qi Qian (2023), 印尼官员:中国人从不向我们发号施令,美国官员倒是经常提苛刻条件 “Indonesian official: The Chinese never dictate to us; US officials, on the other hand, often impose harsh conditions”, Guancha.

- Evi Fitriani (2022), “Indonesia’s wary embrace of China”, MERICS Papers on China, edited by Jacob Gunter and Helena Legarda.

- Lowy Institute Indonesia Poll 2021.

- Yuen Foong Khong (2023), “Southeast Asia’s piecemeal alignment”, East Asia Forum.

- Huong Le Thu (2023), “How to survive a great-power competition”, Foreign Affairs.

- Kevin Daly and Tadas Gedminas (2022), “The path to 2075 – Slower global growth, but convergence remains intact”, Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper.

- East Asia Forum (2023), “The Australia–Indonesia relationship is bigger than the bilateral”, East Asia Forum.

- Daniel Hurst (2022), “Indonesian ambassador warns Australia Aukus pact must not fuel a hypersonic arms race”, The Guardian.

- Rod McGuirk (2022), “China slams reported plan for US B-52 bombers in Australia”, AP News.

- Budi Sutrisno (2020), “’Indonesia won’t be a military base for any country’, Retno says, dismissing Pentagon report”, The Jakarta Post.

- Evan Laksmana noted, for example, “The implicit assumption we are hearing from the US and its allies and partners is that an upswing in military co-operation with ASEAN nations will lead to a broader strategic alignment. That is a flawed assumption.” In Emma Connors (2023), “China steps up regional Asian investment to counter US influence”, Australian Financial Review.

- Darren Lim (2023), “Economic security and hedging in Southeast Asia”, East Asia Forum.

- Evelyn Goh (2023), “Southeast Asia schools Australia on its search for strategic equilibrium”, East Asia Forum.