What should Australia do about…

PRC and US climate ambitions?

by Thom Woodroofe

The new administration of Joe Biden and its ambitious agenda to tackle climate change have cast the global spotlight even more firmly on Australia’s climate inaction. So too did Xi Jinping’s pledge last September that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will reach carbon neutrality before 2060, a target that the Australian Government refuses to set its own firm timeline for.

In the years ahead, Australia’s position on climate change is likely to have an impact – in different ways – on Canberra’s individual relationships with Washington and Beijing. In the Australia–US relationship, Canberra’s lack of climate ambition will be an irritant in the alliance, even if early indications from the Biden team suggest it will not allow this to impede US efforts to work with allies in standing up to the PRC.1 In the Australia-PRC relationship, Canberra’s inability to grapple with the implications of the PRC’s increasing actions to tackle climate change means that Australia risks missing both massive economic opportunities and the parallel political opportunities.

Climate change is the most likely arena for cooperation between the US and the PRC. Canberra, too, should use climate change to pursue constructive engagement with Beijing. But this will first require Australia to reassess its own level of ambition in tackling climate change.

Canberra ignores PRC action at its peril

Xi’s pledge that the PRC will reach carbon neutrality by 2060 is groundbreaking. For the first time, the world’s largest emitter has put in place a timeline to decarbonise its economy. Ideally, this deadline would have been closer to 2050, in line with commitments of the G7 economies. The PRC’s propensity for long-term and effective policy planning, as well as its track record of under promising and overdelivering on its climate targets, will hopefully lead to improvement over time.

The economic transformation required by the PRC to achieve Xi’s vision is huge, especially the urgent action required in the short term. According to modelling by Tsinghua University, Xi’s pledge will require the PRC to peak its emissions around 2025 – up to five years earlier than currently planned.2 Separate modelling by the Asia Society Policy Institute shows that this will also require the PRC to urgently reduce its reliance on coal-fired power generation and to phase it out entirely by 2040.3 The carbon-intensive economic recovery seen in the PRC over the past year and the lack of climate ambition in the recent 14th Five Year Plan do not therefore augur well. Nonetheless, while Canberra has reasons to be sceptical, it ignores Xi’s carbon neutrality pledge at its peril.

For too long, many in Australia have questioned the need for Australia to increase its climate ambition in the absence of additional action by the PRC. As Matt Canavan, a government senator and former minister, has said, “Unless you think we can trust China to reduce their emissions there is no way we should reduce ours”.4 Xi’s carbon neutrality pledge undercuts these arguments. The Australian Government’s refusal to adopt a firm timeline for reaching net-zero emissions or to update its existing 2030 medium-term target undermines the credibility of any call from Canberra for greater ambition from Beijing. Australia’s position with respect to the 2030 target also goes against both the letter and spirit of the Paris Agreement.

Australia should not underestimate the economic implications of Xi’s carbon neutrality pledge. Beijing has now effectively signalled the end of Australian coal exports to the PRC in the medium term. These exports – worth $14 billion in 2018/19 – have always been far more important to Australia than to the PRC.5 While the PRC has its own domestic supply, coal is Australia’s second largest export and the PRC its second largest market for this commodity. The Australian Government has itself conceded that simply shifting this supply to markets such as India would “pose a significant risk”.6

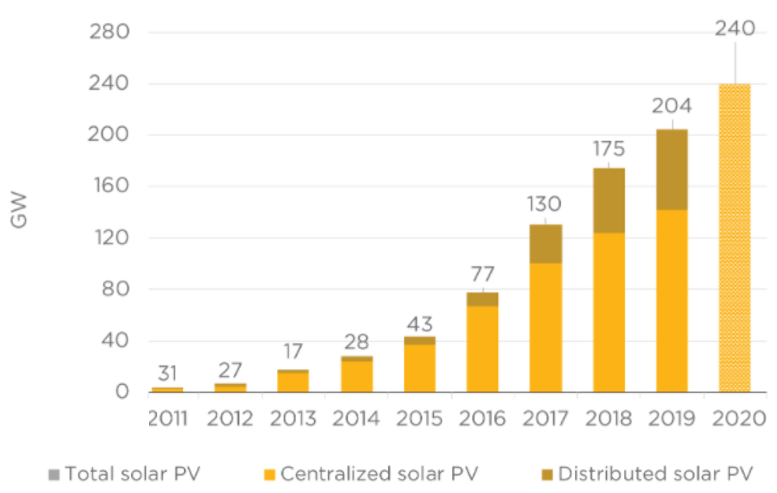

Australia must therefore see Xi’s announcement as a massive opportunity to re-orient both its economic and its political engagement with the PRC. Economically, Australia is ideally placed to seize the opportunities presented by the PRC and become a clean energy “superpower”. The PRC’s installed capacity of solar photovoltaics is expected to increase from around 300 gigawatts today to more than 2500 gigawatts by 2050. Over the same time period solar’s share of the electricity mix is forecast to rise from 3 per cent to more than 32 per cent.7 For Australia to take advantage of this will require it to bolster its low-carbon manufacturing capacity, increase research and development on clean energy technologies, and seize new export opportunities such as green hydrogen or biological raw materials for industrial processes.

PRC solar photovoltaic capacity from 2011-2019, and estimate for 2020

Source: Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy 2020, with data from the National Development and Reform Commission, National Renewable Energy Centre 2020.

Politically, Australia can use climate change as an opportunity for constructive engagement in an increasingly difficult diplomatic relationship. The PRC wants to be seen as a leader in the global fight against climate change, especially in the eyes of its many partners among developing (and climate-vulnerable) countries. Beijing thus has much to gain from climate cooperation with Australia as well as with the US. In the short term, this might include Australia sharing lessons on land-based carbon management or seeking to partner on mutually beneficial projects such as the development of low-carbon steel manufacturing. Scientific, educational and subnational exchanges with the PRC on climate change should also be encouraged.

Xie Zhenhua’s appointment as the PRC’s new climate envoy may provide a fresh political opening given his personal role in founding the now defunct Australia–PRC Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Change, which first met in 2008.

Feeling US pressure

For the past four years, Donald Trump’s climate inaction has provided Australia with the perfect cover to get away with doing very little in the global fight against climate change. More than any other developed economy, Australia will now be in the sights of the Biden Administration to increase its climate ambition. There are five reasons for this. First, Australia is unique among the major developed economies in lacking both short-term climate ambition and long-term vision. While Biden will also want countries such as Japan or South Korea to do more in the short term, these governments have at least made a long-term commitment to net-zero emissions.

Second is the strength of Australia-US political ties encapsulated by the ANZUS alliance. The Biden Administration has indicated it will not let disagreement on climate change get in the way of this relationship. But, if Washington makes clear that it sees greater Australian climate ambition as a matter of the highest political importance, Canberra will presumably face a genuine moment of introspection. In November 2014, Barack Obama did not hold back in making his displeasure about the Abbott Government’s climate ambition known at the Brisbane G20 summit. As the alliance celebrates its 70th anniversary, climate once again risks overshadowing a potential US presidential visit later this year.

Third, the US is likely to have a number of other arrows in its diplomatic quiver that will increase the pressure on countries like Australia. Just as the European Union is considering implementing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, the Biden Administration has signalled that it will explore a tax on carbon-intensive imports. With Australia’s heavily trade-dependent economy, this has the potential to be devastating for many industries, including steel and aluminium.

Fourth is Australia’s habit of using the US as the benchmark for its own climate ambition. In setting Australia’s original Paris target in 2014, the Abbott Government deliberately chose to mirror Obama’s headline pledge of a 26–28 per cent reduction in emissions on 2005 levels. What many missed was that the US planned to achieve this target by 2025, while Australia’s target date was 2030. Biden will table a US target for 2030 at an Earth Day Climate Summit on 22 April in the presence of Scott Morrison. Many expect this to be more than a 50 per cent reduction on 2005 levels – almost double Australia’s current pledge and setting a new benchmark for Canberra in the process.8

Fifth, Australia actually has the capacity to do more to reduce emissions. According to the Government’s own reporting and rhetoric, Australia is on track to “meet and beat” its 2030 target, which prompts the question: why can’t it be increased? In the years since Australia’s original target was adopted, its potential to do more has been underscored by Snowy 2.0 – the largest renewable energy project in Australia’s history, which will start generating power in 2025.

Looking ahead

Australia cannot show up empty handed next month to Biden’s Earth Day Climate Summit or as a guest at the G7 Summit in June and the UN’s Climate Change Conference in November. Continued Australian intransigence on both increasing its 2030 Paris target and committing to net-zero emissions by 2050 will continue to hamper its relations with both the US and the PRC.

There remain individual opportunities to deepen Australia’s engagement with both countries on climate change – including, for example, the Australia-US working group on low-emission technologies proposed by Morrison in his first call with Biden. The efficacy of these efforts will remain limited without a broader political and economic pivot on the part of the Australian Government toward genuinely embracing a low-emissions, climate-resilient future.

As it takes the necessary steps, the Government should not see climate change as purely a zero-sum environmental question. Tackling climate change is now a key geopolitical priority and is becoming a mainstream issue across countries’ national security apparatuses, as demonstrated by the Biden Administration. Indeed, in Southeast Asia, by working with the US to advance the region’s clean energy transformation Australia can also strategically counterbalance the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). And, in the Pacific, by seeking to work with both the US and the PRC, there is an opportunity for Australia to simultaneously bolster the region’s resilience to climate change and enhance its own role as an honest broker.

Recommendations

- The Australian Government should independently commission a range of net-zero pathways for 2050. The tabling by the US of a new 2030 target will set a new benchmark for Australian action and must be seen as an opportunity for Australia to reassess its own target before the UN’s Climate Change Conference in November.

- The Australian Government should change its false narrative about the PRC’s supposed climate inaction, which is closing the door to avenues for economic and political cooperation. Instead, it should seize major clean energy export opportunities with the PRC as its coal export market shrinks.

- Once Canberra and Beijing are talking again, the Australian Government should put forward areas of cooperation with Beijing, for example, on land-based carbon management and low carbon steel manufacturing. The Australia–PRC Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Change could be revived as a forum for this exchange.

- Australia should seek to collaborate with both the US and the PRC on climate change through, for example, the G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group or joint projects on climate resilience in the Pacific. The proposed Australia–US working group on low-emission technologies should include the PRC and others through the freshly reconstituted Major Economies Forum on Energy & Climate Change.

- Australia should also work with the US to apply smart strategic pressure on the PRC to move away from its support for carbon-intensive infrastructure in third countries through the BRI. For example, clean energy finance could be directed to BRI-recipient countries in Southeast Asia.

Author

Thom Woodroofe is Chief of Staff to the President & CEO of the Asia Society and a Fellow of the Asia Society Policy Institute where he manages a project on US-China climate cooperation. Prior to this, he worked in the negotiations of the Paris Agreement, including as an advisor to the President and Foreign Minister of a Pacific Island nation. He studied at Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar.

The views expressed are those of the author. China Matters does not have an institutional view.

China Matters is grateful to four anonymous reviewers who commented on a draft of each text which did not identify the author. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected]

Notes

- Peter Hartcher, “‘Just not going to happen’: US warns China over Australian trade stoush”, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March, 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/just-not-going-to-happen-us-warns-china-over-australian-trade-stoush-20210316-p57b4l.html

- He Jiankun, “Launch of the Outcome of the Research on China’s Long-term Low-carbon Development Strategy and Pathway”, Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development Tsinghua University, 12 October, 2020, https://www.efchina.org/Attachments/Program-Update-Attachments/programupdate-lceg-20201015/Public-Launch-of-Outcomes-China-s-Low-carbon-Development-Strategies-and-Transition-Pathways-ICCSD.pdf

- “U.S. and China Climate Goals: Scenarios for 2030 and Mid-Century”, the Asia Society Policy Institute & Climate Analytics, November 2020, https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/us-and-china-climate-goals-scenarios-2030-and-mid-century

- Matthew Canavan on Twitter, 24 February, 2021, https://twitter.com/mattjcan/status/1364329228250963969

- Matt Coughlan, “Concern over Aussie coal exports to China”, The Canberra Times, 22 May, 2020, https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6765662/concern-over-aussie-coal-exports-to-china/?cs=14231

- “Coal in India 2019”, Australian Government Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, 2019, https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-08/coal-in-india-2019-report.pdf

- Angela Macdonald-Smith, “China’s net-zero goal to send coal, oil demand diving”, Australian Financial Review, 25 September, 2020, https://www.afr.com/companies/energy/china-s-net-zero-goal-to-send-coal-oil-demand-diving-20200924-p55yxf

- “U.S. and China Climate Goals: Scenarios for 2030 and Mid-Century”, the Asia Society Policy Institute & Climate Analytics, November 2020, https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/us-and-china-climate-goals-scenarios-2030-and-mid-century