Source: CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, ANU

Is there a problem with…

Australia’s South China Sea policy?

By Andrew Chubb

Canberra’s current South China Sea policy needs an update. The recent near collision of two American and Chinese destroyers was an apt reminder of the ongoing tensions in the South China Sea. Any military conflict in these waters would jeopardise Australia’s vital economic and strategic interests.

At least US$3.4 trillion in goods transit the South China Sea annually, including two-thirds of Australia’s exports.1 Open and unfettered sea lines of communication are imperative for Australia’s wellbeing. Australia also has a clear strategic interest in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) not taking control of the South China Sea: Australia would be vulnerable to coercion if the PRC military dominated the waterway.

Three layers of disputes lie beneath the tensions in the South China Sea:

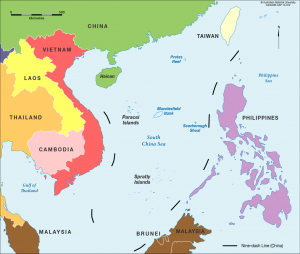

(1) competing claims of the PRC, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia and the Republic of China (Taiwan) to sovereignty over some or all of the islands and reefs there, and the accompanying maritime rights;

(2) energy and fisheries resource disputes between the same five governments, plus Brunei and Indonesia, and;

(3) disagreements between the PRC and the US and its allies over what international maritime law permits, particularly military activities and surveillance, within a state’s 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone. Only this issue directly involves Australia.

At present, Australian policy combines occasionally clumsy diplomatic messaging with calibrated, low-key exercises by the Australian Defence Force to assert navigational rights, as permitted under international law. This is a problem. As the risks of regional conflict rise, Australia needs to tighten its diplomatic language, reserve the right to conduct further exercises of navigation rights in international waters, and better coordinate its operations and crisis responses with Southeast Asia’s ‘middle powers’.

Declarative policy

The official position on the South China Sea disputes over the past decade has been that Australia:

- Takes no position on the question of sovereignty over disputed territories there; but,

- Advocates that disputes be resolved in accordance with international law, including the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper went further and:

- Urged claimants to refrain from actions that could increase tension;

- Called for a halt to land reclamation and construction in the area;

- Opposed use of disputed features and artificial structures for military purposes;

- Expressed particular concern regarding the ‘unprecedented pace and scale of China’s activities’;

- Urged all claimants to clarify the full nature and extent of their claims in accordance with the UNCLOS;

- Stated that the 2016 Philippines v. China arbitration result is ‘final and binding’.

Points 1-3 align closely with collective statements made by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the issue from 2014 to the present, which reflect a lowest common denominator regional consensus. But while points 4-5 broadly align with the ASEAN position, both contain language that makes Canberra’s position different from the modest regional consensus.

One is the call for a ‘halt’ to reclamation. The PRC completed its massive island-building project by 2016. ASEAN’s statements call attention to the consequences of the PRC’s dredging — namely that it has ‘eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions and may undermine peace, security and stability in the region’ — without explicitly demanding a halt to all such activities. Australia should do the same.

Secondly, Australia’s opposition to the use of disputed features for ‘military purposes’ also puts Canberra unnecessarily at odds with others in the region. In reality, every claimant’s presence in the Spratly Islands involves the use of disputed features for military purposes. Australia should instead align its language with ASEAN’s call for ‘non-militarisation’, denoting opposition to new or intensified military deployments.

These semantics are important. The PRC expects to be criticised by the US and its allies, and routinely dismisses such criticisms as out-of-touch with regional opinion. Beijing takes unanimous, region-wide consensus criticisms much more seriously. Aligning Australia’s position as tightly as possible with ASEAN’s would underscore this regional consensus.

Australia should continuously coordinate its diplomatic comments on the South China Sea with key ASEAN countries and ensure region-wide consensus positions are regularly made clear to PRC decision makers, for example at high level meetings. Canberra can still make additional comments beyond ASEAN’s positions — along the lines of points 6-8 — though it should be under no illusions about how these are likely to be interpreted in Beijing.

Demonstrative policy

The centrepiece of the Australian government’s activity in the South China Sea is a program of aerial patrols called Operation Gateway. Originally part of a Cold War effort to hunt Soviet submarines, the program now flies Australian reconnaissance planes out of Malaysia’s Butterworth air base to patrol above the South China Sea, including the Spratly area.

These aerial patrols are regularly interrogated by People’s Liberation Army units. Australian pilots have been recorded responding with assertions of ‘international freedom of navigation rights’ under the UNCLOS and the Convention on International Civil Aviation.

The practice is important to maintain Australia’s insistence on multilateral open access to international waters and assert the UNCLOS’s provisions for free navigation beyond the 12 nautical mile territorial sea limit of any land feature. It demonstrates that Australia does not recognise any attempt to enclose either the Spratly archipelago, or the entire area within the PRC’s nine-dash line, as territorial seas. The low level of fanfare accorded to the patrols by Canberra has helped ensure they have not become a major issue of contention between Australia and the PRC.

Australia also has other options to more forcefully assert navigational rights with equally clear backing under the UNCLOS. One option would be to send patrols within 12 nautical miles of a submerged feature, such as the PRC-controlled Mischief Reef, which is not entitled to a territorial sea. Another would be to conduct patrols using ships instead of, or in addition to, aircraft, as Labor defence spokesman Richard Marles has advocated.

For the time being, it may be more useful for Australia to reserve the right to conduct these additional types of lawful navigation—for example, if the PRC were to declare straight territorial sea baselines enclosing all or part of the Spratly Islands. The PRC has made clear that it would strongly prefer Australia not conduct such actions, and as such the possibility offers Australia a rare point of leverage with the PRC.2

If Australia does opt to further assert freedom of navigation, it should be conducted independently or with other regional countries. Joint patrols involving only the US and Australia would appear provocative and out of step with the region.

What are the risks?

The gravest risk to Australia’s interests — and every other country in the region — is military conflict. The danger of US-China conflict is set to increase as Donald Trump’s trade tariffs and other policies reduce the economic interdependence that for decades has been an incentive to avoid conflict. The president’s mercurial temperament, combined with domestic political problems, could spur aggressive US behaviour. The administration’s inexperience also raises questions about its ability to defuse a crisis.

The use of military pressure by the PRC cannot be ruled out. The PRC used military force against Vietnam in the Paracels in 1974 and the Spratlys in 1988. Given Xi Jinping’s ambitions, the PRC may decide to forcefully evict one or more claimants from their outposts. Alternatively, unilateral PRC moves — such as reclamation on a currently unoccupied reef — may spur other claimants to seek or accept conflict. Domestic instability inside any of the claimant states could prompt adventurism. The increasing presence of military units from all sides, including the US Navy, could also give rise to an accident at sea that escalates out of control.

In these and other scenarios, Australia would be faced with significant pressures both for and against intervention. There are circumstances under which it may make sense for Australia to participate, such as to oppose a naked act of aggression. But the causes of an emerging conflict may be unclear, and it would be difficult to assess the eventual scope and duration of conflict at the outset.

While President Trump’s inexperience has added to the risks of military conflict, his administration’s ‘America First’ doctrine and transactional approach to foreign policy have also raised the risk of a US strategic withdrawal from the region. This forces Australia to consider East Asia, as Hugh White has put it, ‘without America’.

It is possible that a PRC-dominated South China Sea would be benign for non-claimant countries like Australia. But how Beijing would use such a position of power is unclear. Australia needs to carefully examine future scenarios in which the United States alone does not provide stability in the South China Sea and instead stability relies on relatively unconstrained PRC preferences — and the responses of other regional states.

Australia’s exercise of UNCLOS-mandated navigational freedoms may result in PRC economic retaliation. Beijing has significant means to punish certain sectors of the Australian economy, principally education, tourism and high-end consumer goods. If Canberra wants to position itself as a defender of the international maritime order, it must consider how it would respond to potential PRC economic counter measures.

In sum, Australia’s aerial patrols in the South China Sea to assert navigational rights are measured and backed by international law. However, there are unnecessary differences between Australia’s declarative policy and the regional consensus expressed in ASEAN’s official statements.

What does this mean for Australia?

Recommendations

- Australia’s diplomatic messaging should be more consistent with ASEAN’s consensus. This does not mean limiting Australia’s public comments to those contained in ASEAN statements, but rather the adjustment of language to underscore key points of regional unity to Beijing.

- Australia should seek to more closely coordinate its South China Sea policy with Indonesia. Bilateral leaders’ discussions should routinely cover the issue. A bilateral working group should be established to solely focus on China policy issues.3

- Australia’s officials should routinely encourage the PRC to clarify the meaning of its nine-dash line, and emphasise the concerns and mistrust that its current ambiguity generates. This could be coordinated with Indonesia.

- Australia’s political leadership should subtly, but firmly, reserve the right to exercise lawful navigational rights around claimed features of the PRC, as permitted according to the UNCLOS. Such patrols should be conducted either independently or with other regional countries, rather than jointly with the US only.

- Federal government departments should together with the ADF intensify efforts to plan for different types of crises in the South China Sea. These efforts should make use of recent innovations in crisis simulation design and experimental methods.

- Australia’s civilian maritime administrative agencies should provide training and organisational expertise to regional law enforcement agencies, especially those of the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia.

- Australia should advocate for a fisheries cooperation scheme based on harmonisation of existing unilateral fishing restrictions such as the PRC’s annual ban on certain types of commercial fishing north of the 12th parallel. This would offer a potential stepping stone to joint fisheries management.

Author

Dr Andrew Chubb is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program, and a Fellow of the Perth USAsia Centre. His research examines the linkages between PRC domestic politics and security issues in East Asia, with a focus on strategic communication in maritime and territorial disputes.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion of Australia’s policy on the South

China Sea. Our goal is to influence government and relevant business, educational and non-governmental sectors

on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to the following reviewers who received the draft text anonymously for their

comments on the draft: James Goldrick, Baogang He, Greg Raymond, Bec Strating, Jingdong Yuan, Jian Zhang.

We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to

[email protected].

Notes

- ‘2016 Defence White Paper’, Australian Department of Defence, February 2016, p. 57.

- Andrew Chubb, ‘South China Sea patrols are an option, with or without Trump’, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 May 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/south-china-sea-patrols-are-an-option-with-or-without-trump-20170528-gweqy7.html

- Linda Jakobson and Bates Gill, China Matters: Getting it Right for Australia, Black Inc. / La Trobe University Press, 2017, p. 191.