Source: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Tim D. Godbee, US Pacific Fleet

What should Australia do about…

PRC development activities in the Pacific?

By Jennifer Hsu

The Australian government worries that the official development assistance (ODA) and other economic activities of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will gradually undermine Australia’s influence in the Pacific, a region central to Australia’s interests. Canberra also frets that Beijing may use its economic power to compel one of the Pacific Island nations to host a PRC naval base. Compounding the government’s concerns is rising frustration among Pacific Island nations toward Australia’s climate change stance – e.g. Australia barred any mention of coal vis-à-vis climate change in the 2019 Pacific Islands Forum final communiqué.

The Pacific Step-Up is Australia’s response to the PRC’s sustained economic interest in the region. Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the next phase of the Pacific Step-Up program in November 2018. It aims to increase Australia’s outreach, influence and provide opportunities to the Pacific Islands. Canberra has expanded Australian labour programs for Pacific Islanders, established a new infrastructure fund, and promised to extend Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) electricity grid.

It is in Australia’s interest to ensure that the Pacific Islands are affluent and resilient. Even though Canberra views the PRC as a strategic competitor, there are instances where partnering with the PRC would help achieve these goals.

Where possible, Australia should work with the PRC towards shared development goals. This brief outlines the PRC’s bilateral ODA, multilateral co-operation, and finally, the emergence of its NGOs in international development. The brief’s focus is on the Pacific.

The PRC’s ODA in the Pacific

Broadly quantifying the PRC’s global ODA is complex because it is opaque and does not always conform to the OECD Development Assistance Committee’s definition.

However, it is clear that the PRC’s ODA is substantial and mainly bilateral. The PRC committed an estimated US$350 billion in official development finance to 140 countries between 2000 and 2014. From 2009-2014, an average of 93 per cent of the PRC’s aid went to bilateral co-operation.1

Despite the size of global PRC aid, concerns that Beijing will economically dominate the Pacific are overblown. Australia was the largest provider of ODA with US$7.38 billion between 2011 and 2017, compared to the PRC’s US$1.6 billion over the same period.2

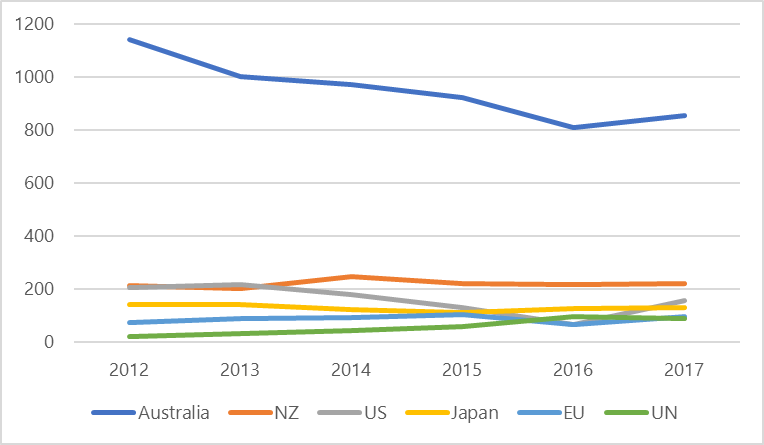

Figure 1: ODA Grants to the Pacific, Total Aid Spent 2012-2017 (USD million)

Source: Calculations based on Lowy Institute, Pacific Aid Map, 2012-2017

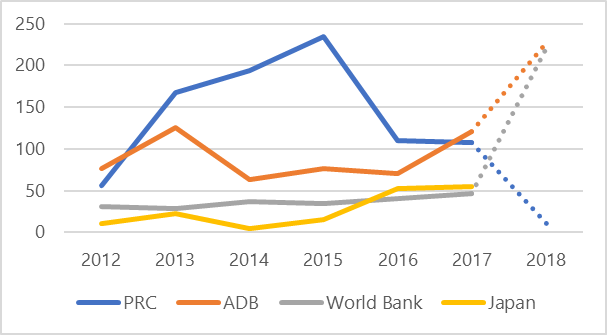

Moreover, PRC aid in the Pacific has dropped in recent years (see Figure 1). Until recently, Australian aid was mostly delivered via grants, while the PRC’s aid was via concessional loans. Figure 2 shows that PRC lending dropped significantly from 2015 to 2017 and data for 2018, while still incomplete, shows an even steeper drop. The reduction in PRC lending is a trend anecdotally evident elsewhere in the world.3

Figure 2: Government Loans to the Pacific, Total Aid Spent, 2012-2018 (USD million)

Source: Calculations based on Lowy Institute, Pacific Aid Map, 2012-2018

N.B. Data for 2018 is incomplete, but indicates a downward trend in PRC ODA loans

With PRC lending declining, debt diplomacy concerns in the Pacific Islands are premature. Research from the Lowy Institute and the Australian National University indicates that only a handful of countries in the Pacific with PRC loans also have high levels of debt distress. Tonga, Samoa and Vanuatu are the three small Pacific economies that appear to be among those most heavily indebted to the PRC, regionally and globally.4

Australia recently promised to loan AU$440 million to PNG to assist with its budgetary issues. While yet to materialise, the PRC pledged US$3.9 billion in loans to PNG in 2017.

Developmental and infrastructural challenges in the Pacific are immense. Traditionally, Australia and other Western donors have been reluctant to fund infrastructure and instead focused on civil society and governance. The Australian government is trying to change this. In 2018, it established the $2 billion Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP). The AIFFP is still in its early stages and it is unclear whether it will effectively build infrastructure.

Compared to Australia, a greater share of the PRC’s ODA in the Pacific has gone towards infrastructure. One Pacific Island official told the author she appreciates the PRC’s commitment to infrastructure but welcomes Australian building standards. In addition to the AIFFP, Australia could begin to promote better construction standards across the Pacific with the trilateral Blue Dot Network and involve the US and Japan.

The PRC government recognises problems in its ODA, for example concerns about the quality of PRC-built infrastructure and the corporate social responsibility of PRC firms. Moreover, projects tend to rely on PRC materials and labour, although in some cases, a shortage of skilled workers in the recipient country necessitates the use of PRC labour. ExxonMobil also imports foreign workers due to skill shortages in PNG.5 Nonetheless, Pacific nations, such as Fiji, welcome the PRC’s infrastructure funding.6

The PRC government is trying to tackle the weaknesses in its development programs. It established the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), a bilateral aid agency with vice-ministerial level status. The centralisation of most of the PRC’s development assistance may improve planning and co-ordination. A debt sustainability report issued by the PRC government states that the PRC seeks to strike a “balance between meeting financing demands, sustainable development and debt sustainability” for recipient countries.7

The PRC’s multilateral co-operation

The Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB), which the PRC created in 2015, exemplifies Australia and the PRC’s ability to collaborate even when bilateral relations are tense. Both the PRC and Australia are founding members of the AIIB. The multilateral development bank (MDB) solely focuses on infrastructure; loans are extended at commercial interest rates; the PRC has the largest vote share of 26.6 per cent, giving it effective veto power. However, most of the AIIB’s projects are co-financed with established MDBs – 17 of the 25 projects as of mid-2018 – where the rules of the partner MDBs govern.8

The PRC has in certain cases agreed to co-operate trilaterally in the Pacific. The PRC-New Zealand-Cook Islands Water Partnership launched in 2014 is purported to be the PRC’s first trilateral development partnership with a traditional donor.9 The project upgraded Rarotonga’s water supply network. New Zealand contributed to the grant element of the loan, and the PRC provided the concessional loan element and the technical expertise. Given this is an area where both the PRC and New Zealand have experience, it presented a relatively low risk entry for all parties.

Similar co-operation between Australia, the PRC and PNG in malaria control since 2016 demonstrates the possibilities of trilateralism which serves Australia’s interests. The trilateral partnerships were initiated by the Cook Islands and PNG respectively. The Australia-PNG-PRC malaria program’s 2018 mid-term review states the project is “a successful model of trilateral development cooperation …the trilateral project has demonstrated the additional value made possible when these two donors [Australia and the PRC] work together in partnership with the PNG government. There would be merit in further application of this model.”10

Collaboration on health can improve life expectancy and reduce aid duplication. The Australia-PNG-PRC malaria trilateral model of co-operation can extend to treating non-communicable diseases (NCDs) e.g. diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. PNG’s first NCDs national survey indicated 77.7 per cent of the population were at high risk.11 The PRC is a potential partner because of its long experience with NCDs.

Trilateral co-operation is challenging but meaningful, even in small steps. It can benefit the region and is therefore in Australia’s interests. The current modest examples of trilateral development co-operation in the Pacific suggests traditional donors are willing to partner with the PRC. In the future, some of the opportunities could involve PRC NGOs.

Civil society

The prevalence of natural disasters in the Pacific provides Australia an opportunity to work with the PRC government and NGOs in preparation, response and rebuilding efforts. This can occur simultaneously as Australia counters other PRC actions in the region.

NGOs in the PRC are different to NGOs in most liberal democracies because they do not operate completely without state guidance and oversight. Their international role is nascent but growing.

PRC NGOs are active in emergency humanitarian efforts. The experience of dealing with the aftermath of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake enabled a learning process for NGOs, which proved useful when they responded to assistance requests after the 2015 Nepalese earthquake. The China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, the Amity Foundation and the One Foundation were at the forefront of the PRC’s international efforts. The Nepalese experience offered PRC NGOs lessons in working with different international and Nepalese partners.12

PRC NGOs have started to call for PRC firms working abroad to integrate greater corporate social responsibility (CSR) into their operations. For example, the Beijing-based Global Environmental Institute (GEI) has partnered with PRC government departments to design and deliver workshops on CSR to help PRC firms comply with PRC environmental and social regulations and be socially responsible to host communities.13 Furthermore, GEI works with the Burmese government and NGOs in the sustainable timber trade and mangrove conservation. PRC government data indicates that only 50 per cent of the companies surveyed, which operate in BRI countries, conduct a social impact assessment.14 Clearly, there is space for PRC NGOs to engage with their international counterparts, including Australian NGOs, to meet development challenges.

Aside from the PRC’s US$100,000 donation to Vanuatu’s 2015 Cyclone Pam relief efforts via the Red Cross Society of China, it is difficult to find PRC NGO activity in the Pacific. This is the moment for both the Australian government and Australian NGOs to explore collaborations in development and humanitarian aid with their PRC counterparts to positively impact regional development. Natural disaster risk management is a suitable area of collaboration. The Pacific Community’s Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific outlines guiding principles for various stakeholders, “which can reduce duplication and optimise use of limited resources and sharing of technical expertise.”15

Conclusion

The Australian government and NGO community can fruitfully engage on certain issues with their PRC counterparts to try and meet development goals across the Pacific. Adopting the PRC competitor narrative is unhelpful to achieving development outcomes. Discussions with Australian international development NGO representatives indicate that there is genuine interest in potential collaboration with their PRC counterparts. Three areas where collaboration and possible impact can be made include: trilateral cooperation; engagement with PRC NGOs; and working with governments in the region to better negotiate bilateral finance with the PRC.

Policy recommendations

- Australia, PNG and the PRC should build upon the trilateral model of co-operation in malaria control to deliver aid to combat non-communicable diseases in PNG.

- Australia should seek advice from Pacific Island countries on which projects they deem suitable for trilateral co-operation with the PRC and encourage these countries to initiate formal discussions to establish these projects.

- The Australian NGO sector should identify key PRC NGOs as potential collaborators to undertake future humanitarian disaster relief work in the Pacific Islands.

- Australian and PRC researchers with social policy and NGO expertise are already collaborating to understand best practices in both countries. The next step is to look outwardly at how Australian and PRC NGOs could partner in the Pacific in the most

productive way. Given the regional complexities of the Pacific, PRC NGOs would benefit from the expertise and training delivered by Australian and Pacific Islands’ NGOs in specific areas, including natural disaster relief and corporate social responsibility. - Australia should actively work with the PRC, other governments in our region, and NGOs to comply with the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific. Moreover, the Australian and PRC governments could consider establishing a natural disaster fund to assist in infrastructural repair. The fund should be co-ordinated by Pacific Island countries so that it aligns with regional and national priorities.

Author

Dr Jennifer Hsu is a Policy Analyst at China Matters. After completing her PhD at the University of Cambridge in Development Studies, she researched and taught in development studies, political science and sociology in North America and the UK. Her research expertise broadly covers state-society relations, state-NGO relations and the internationalisation of Chinese NGOs.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion on PRC aid in the Pacific and its implications for Australia. Our goal is to influence government and relevant business, educational and nongovernmental sectors on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to five anonymous reviewers who received a blinded draft text and provided comments. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected]

Notes

- Axel Dreher et. al., “Aid, China, and growth: Evidence from a new global development finance dataset,” Aid Data Working Paper 46 (2017); Naohiro Kitano and Yukinori Harada. 2016. “Estimating China’s foreign aid 2001–2013.” Journal of International Development, 2016, 28(7): 1050-1074.

- Lowy Institute, Pacific Aid Map, https://pacificaidmap.lowyinstitute.org/

- Cissy Zhou, “China slimming down Belt and Road Initiative as new project value plunges in last 18 months, report shows,” South China Morning Post, 10 October 2019, https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3032375/china-slimming-down-belt-and-road-initiative-new-project

- Roland Rajah, Alexandre Dayant, Jonathan Pryke, “Ocean of debt? Belt and road and debt diplomacy in the Pacific,” Lowy Institute, 21 October 2019, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/ocean-debt-belt-and-road-and-debt-diplomacy-pacific#_ednref19

- Carmen Voigt-Graf and Francis Odhuno, “PNG LNG and skills development: a missed opportunity,” Devpolicy Blog, 27 March 2019, https://devpolicy.org/png-lng-and-skills-development-20190327/

- Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, Q&A Pacific, ABC, transcript 2 December 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/qanda/2019-02-12/11730632

- Ministry of Finance, Debt Sustainability Framework for Participating Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative, 25 April 2019, http://m.mof.gov.cn/czxw/201904/P020190425513990982189.pdf

- Shahar Hameiri and Lee Jones, “China challenges global governance? Chinese international development finance and the AIIB,” International Affairs, 2018, 94(3): 573-593.

- Denghua Zhang, “China–New Zealand–Cook Islands Triangular Aid Project on Water Supply,” ANU In Brief 2015/57, http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2016-07/ssgm_ib_2015_57_zhang.pdf

- Francis Hombhanje et. al. Mid-Term Review of the Australia China Papua New Guinea Pilot Cooperation on Malaria Control, June 2018, https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/australia-china-png-pilot-cooperation-on-the-trilateral-malaria-project-independent-mid-term-review.pdf

- WHO, Papua New Guinea NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report, (Port Morseby: PNG, 2014), https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/PNG_2007-08_STEPS_Report.pdf

- Tom Bannister, “China’s own overseas NGOs: The past, present, and future of Chinese NGOs ‘going out.’” In CDB Special Issue on Chinese NGOs Going Out. (Beijing: China Development Brief), 1-15.

- Global Environmental Institute, “Corporate Sustainability Training,” http://www.geichina.org/en/program/oite/corporate-sustainability/ ; Global Environmental Institute, “China-Myanmar Timber Governance,” http://www.geichina.org/en/program/oite/china-myanmar/ ; “Mangroves and Forest Conservation,” http://www.geichina.org/en/program/eccd/mangroves-forests/

- Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, MOFCOM (CAITEC), Research Centre of the SASAC, and the UN Development Programme China. 2017 report on the sustainable development of Chinese enterprises overseas: supporting the Belt and Road regions to achieve the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, http://www.cn.undp.org/content/china/en/home/library/south-south-cooperation/2017-report-on-the-sustainable-development-of-chinese-enterprise.html

- Pacific Community (SPC), Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific: An Integrated Approach to Address Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management [FRDP] 2017 – 2030. (Suva, Fiji: Pacific Community, 2017), p.7.