STANCE #32 – DECEMBER EDITION

By Harrison Rule

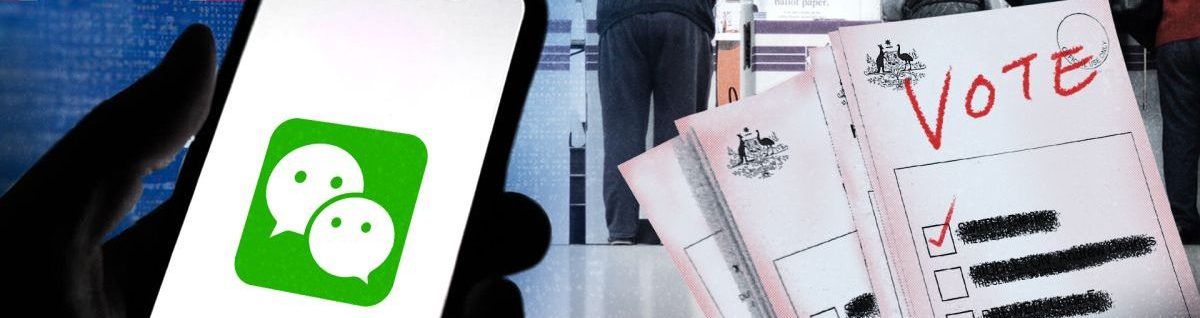

At the height of the 2019 Australian Federal Election, both major parties took the tussle for Chinese-Australian voters to the social media platform WeChat – and both left crying foul. Labor Party hopeful Bill Shorten’s campaign was undermined by doctored screenshots fabricating his position on immigration. Scott Morrison’s campaign confronted inflammatory articles insisting his government was ‘kicked in the head by a Kangaroo’.

Some Australian media outlets were quick to characterise this Chinese-language cyber trolling as part of Beijing’s “robust and sophisticated” propaganda strategy. The reality is significantly more complex.

Mainland Chinese users make up almost a quarter of global internet traffic, with 800 million registered PRC phone numbers on WeChat alone. As such, the line between PRC state-coordinated information warfare and impassioned Chinese netizens has become blurred. In order to maintain the integrity of our democratic dialogue, we must avoid conflating all Chinese dissonant online behaviour as part of a PRC state-coordinated cyber agenda.

A nuanced acknowledgement of the PRC’s growing cyber-presence is crucial to avoid mislabelling innocuous online Chinese commentators as threats. In August, Twitter suspended 936 accounts believed to be part of a “PRC state-backed operation”. The Chinese citizen account owners decried the move as “shamefully hypocritical” and used the ban to mobilise patriotic responders – aggravating and potentially further radicalising others.

When we rush to denounce the most aggressive online voices as state-sponsored propaganda, we neglect to recognise individuals – many of whom may be engaging in democratic dialogue for the first time. The Australian government has a significant role to play in guiding Australian institutions towards technologies that will help differentiate between individuals expressing genuine beliefs and PRC state-sponsored propaganda, allowing Australians to make more informed decisions on how to report on PRC-related hostility online.

The Morrison government and relevant federal departments can source guidance from Canberra’s cyber agencies on how open-source aggregation and natural language processing solutions can be used to differentiate between state-sponsored and private citizen behaviours. Such tools are used extensively by law enforcement agencies around the world and identify formulaic language patterns across millions of posts. For example, an account that made 2,000 pro-PRC comments with limited variation in language from available Beijing-sponsored comment datasets could be flagged, allowing Australian institutions to make informed assumptions about the origins of the posts. By involving broader non-government organisations in the learning process, political parties, media organisations, and non-government bodies would be able to make more informed decisions on how to report on cyber issues, avoiding the conflation of a broad range of online users into a single cyber ‘bogeyman’.

Previously leaked provincial government documents showed the techniques of state-supported group the 50 cent Party (五毛党), which can be detected through using a combination of these technologies.

Of the over 43,700 state-sponsored comments posted by the 50 cent Party identified from the above leaked documents, virtually none resembled the styles of the aggressive WeChat onslaught observed in the lead-up to the 2019 Federal election. Conversely, researchers Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts found that 94% of the leaked comments could be described as ‘non-argumentative praise’. Only a tiny fraction of these verified state-sponsored comments involved taunting or attacking foreign nations or leaders.

Equally, in cases of fervent online hostility, these technologies can lay the groundwork for organisations to initiate sophisticated discussions regarding the origins and risks of online commentary. For example, pro-PRC online citizen groups such as Little Pink (小粉红) have a legacy of using personal accounts to coordinate hostile online behaviour, but ultimately do not have clear connections to official PRC propaganda channels.

Our current inability to consider the motivations and origins of those behind the screen sets us on a dangerous trajectory. Lowy Institute polling suggests Australians’ trust in China has fallen to a record low, much of which can be attributed to the continuing debate about foreign interference in Australian politics. If trusted Australian institutions continue to feed into a narrative of pervasive PRC coercive behaviour, we risk exaggerating the threat of genuine Beijing-backed information warfare campaigns. Without decisive, government-backed acknowledgment of the complexity and nuance at play in the Chinese-language internet, we may breed a more hawkish and defensive public consciousness towards Australia’s most valuable economic and educational partner.

When Australian civil discourse is transposed online, it inevitably becomes part of a global debate in an increasingly contested cyber space. Natural language processing and open-source aggregation tools provide a means to lift the veil on the Chinese-language sphere online and empower Australian institutions to actively temper the foreign interference narrative.

Harrison Rule is an Associate Consultant in PwC Australia’s Cyber Practice. Prior to this, he worked in Public Policy research positions in Taiwan on behalf of the Australia New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and a number of Cybercrime research institutes. Harrison is a recent graduate of a Bachelor of Asian Studies (Mandarin) and a Bachelor of International Security Studies from the Australian National University.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not represent the views of PwC Australia or China Matters.

Photo: CNN