Image source: Terence H on Flickr

What should Australia do about…

PRC nationalists?

By Yun Jiang

In Australia’s universities, Chinese communities and wider society, nationalists from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) sometimes aggressively counter the expression of independent and critical opinions about the PRC and the Communist Party of China (CPC). It can be difficult to differentiate between a committed nationalist acting for a cause and someone commissioned by the PRC government.

PRC nationalism promotes the perceived interests of “China” as a nation, mostly along the line of what the CPC decrees. It is rooted in China’s recent history that highlights Western aggression against China since the mid-19th century.1 PRC nationalists are usually concerned with issues related to sovereignty and national pride. Some nationalists are easily offended at any perceived slight against the PRC or PRC nationals.

Actions by nationalists who glorify the PRC create at least two problems in Australia. First, people motivated by PRC nationalism have intimidated individuals and groups who speak out against the CPC or who are perceived as critical of the PRC. This is having a direct effect in the lecture halls and seminar rooms of Australian universities. While it most directly targets other PRC citizens studying or working in Australia and Chinese Australians, its effects can be felt in wider society. For example, Australian swimmer Mack Horton received death threats from PRC nationalists after calling Sun Yang, a swimmer from the PRC, a “drug cheat”.

Second, Australian media and commentators sometimes portray people of Chinese heritage who support PRC policies or who express nationalistic sentiments as brainwashed or threats to democracy. This stereotyping has alienated members of the Chinese diaspora in Australia who feel they do not have the right to express a positive view of the PRC, which of course they do.2 People are entitled to hold whatever view they want in a liberal democracy, provided they do not infringe on the rights of others.

Any policy response needs to proportionately balance protecting the victims of intimidation with the rights of individuals to peacefully express their views of the PRC without being labelled as threats to democracy.

How is PRC nationalism different from other forms of nationalism?

While intimidation and harassment are used by nationalist groups around the world, the PRC’s authoritarian nature and its global reach add an extra layer of threat. For example, a person who attended a Hong Kong democracy event in Australia was harassed by PRC nationalists and then soon after the person’s family was contacted by authorities in the PRC.3 Another, well-documented case is that of researcher Vicky Xu, who has written and voiced her criticisms of the PRC. She has received death threats from nationalists in Australia and warnings from PRC authorities.4 Her recent pro-Hong Kong views have resulted in intimidation of her and her family members.

PRC government tactics of going after those who speak out against it are at times aided by PRC nationalists in Australia. These nationalists may have come across those who disagree with the PRC in their classrooms or chat groups or within their communities, and have decided to punish them for their views by publishing their personal details online or reporting them to a PRC consulate. A PRC student told academic Kevin Carrico that her presentation on self-immolation of Tibetans in his class at Macquarie University was reported back to her family in the PRC.5

There is no data available to analyse the seriousness of this problem. Anecdotes suggest that it is getting worse. ANU Professor Sally Sargeson wrote in 2017 that the number of PRC students who express concern about surveillance is increasing:

I teach an undergrad class on Chinese politics. Part of the assessment for this class is based on students’ contributions to tutorial discussions. Every year, a significant proportion of the class is made up of Chinese citizens, and increasingly over the past few years, some of these students have come to me asking to be included in a tutorial group that contains no other Chinese citizens, so they can speak freely.6

As a result of actions by PRC nationalists in Australia, individuals who maintain a strong connection to the PRC have a strong incentive, when speaking publicly, to stay within the bounds of acceptability from Beijing’s viewpoint. Their speech and actions are monitored by PRC nationalists who may be acting alone. This leads to fear and self-censorship in Australia.

These PRC nationalists’ belief that what they are doing is justified is partly due to the CPC’s encouragement to conflate the concept of “China” with the state (PRC), the party (CPC) and the people (Chinese, usually Han, the overwhelmingly largest ethnic group in the PRC). For example, the PRC party-state often characterises criticisms of its policies as “hurting the feelings of Chinese people”.7 Abuse tends to be more extreme if it is directed at a member of the Han ethnic group. The term “Hanjian” or “Han traitor” is often applied to people of Han ethnicity who are perceived to be working against the PRC’s interests.8

The “double standard” problem

In a 2017 speech, Julie Bishop, then Minister for Foreign Affairs, argued, “we don’t want to see freedom of speech curbed in any way involving foreign students or foreign academics”.9 However, some in the diaspora perceived that freedom of speech was only protected for those who speak out against the CPC. A partial translation of the speech was featured on a well-known WeChat account. The most popular comment below the article was: “We respect their values and free speech. So, when we state our own opinions, why don’t they respect that? Total double standard.”10

Commentators do label PRC students as brainwashed. For example, Clive Hamilton of Charles Sturt University argues that Australian sovereignty is being eroded by “billionaires with shady histories and tight links to the [CPC], media owners creating Beijing mouthpieces, ‘patriotic’ students brainwashed from birth, and professionals marshalled into pro-Beijing associations set up by the Chinese embassy”.11

Another widely held assumption is that many migrants from the PRC are not committed to the values of democracy. Journalist Peter Hartcher contends that the Australian government should “consider changing the composition [of migrant intake] in favour of Chinese immigrants from places other than mainland China” and that “preference should not only be given to immigrants with the most suitable work skills but also to those with the most compatible values. Immigrants who are committed to liberal-democratic principles should always be given priority over those who are not.”12 This kind of environment makes it difficult for people of Chinese heritage to speak positively about the PRC without being labelled as a threat to democracy. That may not be the intention of these commentators, but it is an outcome.

Fran Martin of Melbourne University has studied the social experience of PRC university students in Australia. She writes:

Most find the claims [that they are spies for or controlled by the CPC] strange, unfair, and implausible. Most confusing is the charge that by voicing their political opinions in the classroom, Chinese students are undermining the free speech of others. “Isn’t expressing our own opinions an instance of free speech, rather than an attack on it?” asked one student. 13

Members of Chinese communities in Australia often feel trapped between PRC nationalists, the PRC government and popular stereotypes. One Chinese Australian told a China Matters researcher that they cannot speak publicly on sensitive issues such as Taiwan because they would be accused of being a PRC stooge (if they were pro-unification) or unpatriotic (if they were pro-independence). Another Chinese Australian said that freedom of speech must include the right to agree with the CPC or agree with actions by the PRC government.

Chinese language media in Australia

Much of the Chinese-language media in Australia is influenced, either directly or indirectly, by the PRC. Due to language and cultural differences, many recent arrivals from the PRC do not consume Australian English-language media, at least initially. They prefer PRC state media or other Chinese-language material produced in Australia.

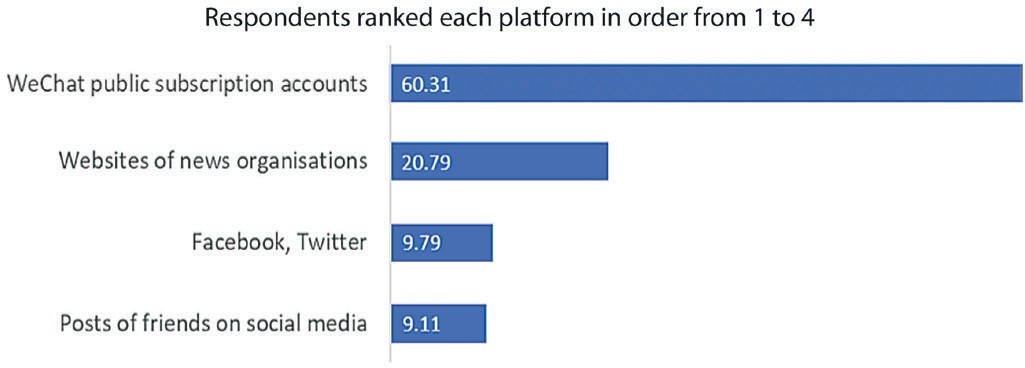

WeChat is the most commonly used platform for receiving news among the Mandarin-speaking communities in Australia. A survey of 522 Mandarin-speaking people living in Australia found that 60 per cent of the respondents use WeChat public subscription accounts as a primary source of news and information (see figure).14

WeChat is a platform owned by Tencent, a PRC company. Due to its size and reach, the PRC government closely scrutinises the operation of WeChat.15 Articles posted on WeChat can be removed by administrators if they are deemed to be overly critical of the PRC government or its leadership. Even content producers in Australia have to self-censor.

Ranking of media platforms accessed by Mandarin speakers in Australia

Source: Wanning Sun, “How Australia’s Mandarin speakers get their news,”

The Conversation

Outside the WeChat system, PRC government entities have signed content-sharing agreements and partnerships with Chinese-language media outlets in Australia. And those, too, often publish the PRC government line. Privately owned Chinese-language media outlets that are critical of the PRC government in Australia, such as Vision Times, report that advertisers are being told by the PRC government to cease their association with those outlets.16 This makes it difficult for independent Chinese-language media to financially survive in Australia. In turn, some pro-PRC media outlets elevate PRC nationalist views and alternative voices are shut out.

Mainstream Australian media outlets such as SBS, the ABC and The Australian also provide Chinese-language news. With very few exceptions, such as SBS Mandarin Radio, most of the news stories are not originally produced in Chinese, but are translated from English. These stories rarely present perspectives from the Chinese diaspora.

Australia’s media regulation, including foreign investment rules on media ownership, only covers the daily press and free-to-air television and radio, not social media. Although the Australian government recognises that the spread of propaganda and disinformation through online platforms is a major threat to our democracy, Australia is still in the early stages of responding.17

The Australian Senate’s Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media will examine foreign interference through social media, but its report is not due until 2022. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has looked at the impact of digital platforms on media competition, but it focused only on Facebook and Google.

As a result of the media consumption patterns as well as censorship pressures, the PRC has increased its influence over what the Chinese diaspora sees, reads and shares in Chinese-language media in Australia. There is a risk that an echo chamber of nationalist voices is being created in the Chinese diaspora.

Recommendations

- Universities should provide mandatory civic education courses for all students. Courses should focus on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, academic freedom and foreign interference laws.

- Universities should take tough action, including expulsion, to punish students who harass or intimidate others, or who report the actions of other students to PRC authorities.

- Lecturers should actively encourage classroom debate while protecting students from potential inter-student surveillance. Anonymous online discussion is one classroom strategy — students remain anonymous to other students but not to the lecturer.

- The National Foundation for Australia–China Relations should take the lead and fund initiatives for Chinese Australian writers and journalists to publish and broadcast (in both Mandarin and English) in media outlets such as the ABC and SBS and in new and emerging media outlets. News should be diversified and the relevance of the reports to Chinese Australians should be improved.

- Upcoming digital platform legislation should include rules for platforms used by the Chinese diaspora in Australia such as WeChat.

- The Senate’s Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media should complete its report by the end of 2020. This is too important to wait until 2022.

- The Counter Foreign Interference Taskforce should investigate and work towards publicly penalising those who report the details of individuals to PRC authorities, in order to deter others.

Author

Yun Jiang is an editor of the China Story blog. She is also a director of the Canberra-based China Policy Centre that produces China Neican, a policy-focused China analysis newsletter. She was formerly a policy adviser in the Australian Government. Yun has a Master of Public Policy in International Policy and Master of Diplomacy from Australian National University.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion on PRC nationalism and its implications for Australia. Our goal is to inform government and relevant business, educational and nongovernmental sectors on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to five anonymous reviewers who commented on a draft text which did not identify the author. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected].

Notes

- Suisheng Zhao, “Nationalism’s Double Edge Sword”, Wilson Quarterly, Autumn 2005, http://archive.wilsonquarterly.com/essays/nationalisms-double-edge

- Fran Martin, “ Overstating Chinese influence in Australian universities”, East Asia Forum, 30 November 2017, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2017/11/30/overstating-chinese-influence-in-australian-universities/

- Melissa Clarke, “Australia requests Beijing let family of Uyghur man leave China following Four Corners program”, ABC News, 17 July 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-17/uyghur-china-response-four-corners-xinjiang-detention/11316752; Fergus Hunter, “A student attended a protest at an Australian uni. Days later Chinese officials visited his family”, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 August 2019, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/this-student-attended-a-protest-at-an-australian-uni-days-later-chinese-officials-visited-his-family-20190807-p52eqb.html

- Jennifer Feller and Susan Chenery, “From ‘perfect Chinese daughter’ to Communist Party critic, why Vicky Xu is exposing China to scrutiny”, ABC News, 10 March 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-09/vicky-xu-exposing-chinas-human-rights-abuses/11954794

- Elizabeth Redden, “China’s ‘long arm’”, Inside Higher Ed, 3 January 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/01/03/scholars-and-politicians-raise-concerns-about-chinese-governments-influence-over

- Anders Corr, “Chinese informants in the classroom: pedagogical strategies”, Forbes, 28 June 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/anderscorr/2017/06/28/chinese-informants-in-the-classroom-pedagogical-strategies

- Fergus Hunter and Patrick Begley, “‘Humiliating’: Chinese nationalist trolls target critics in Australia”, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 2019, https://www.smh.com.au/national/humiliating-chinese-nationalist-trolls-target-critics-in-australia-20190819-p52in4.html

- Pal Nyiri, Juan Zhang and Merriden Varrall, “China’s Cosmopolitan Nationalists: ‘Heroes’ and ‘Traitors’ of the 2008 Olympics”, China Journal, no. 63 (January 2010) pp. 25–55

- Andrew Greene and Stephen Dziedzic, “China’s soft power: Julie Bishop steps up warning to university students on Communist Party rhetoric”, ABC News, 16 October 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-16/bishop-steps-up-warning-to-chinese-university-students/9053512

- “Australian Foreign Ministers warns Chinese students”, 17 October 2017, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/kfbIzmS4l4JLEdHFefIu4w

- Quoted in Dylan Welch, “Chinese agents are undermining Australia’s sovereignty, Clive Hamilton’s controversial new book claims”, ABC News, 22 February 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-02-22/book-reveals-extent-of-chinese-influence-in-australia/9464692

- Peter Hartcher “Red flag: waking up to China’s challenge”, Quarterly Essay, no. 76, November 2019, https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/essay/2019/11/red-flag/

- Fran Martin, “How Chinese students exercise free speech abroad”, The Economist, 11 June 2018, https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/06/11/how-chinese-students-exercise-free-speech-abroad

- Wanning Sun, “How Australia’s Mandarin speakers get their news”, The Conversation, 22 November 2018, http://theconversation.com/how-australias-mandarin-speakers-get-their-news-106917

- Bang Xiao, “On WeChat, I’ll stay a silent observer and nothing more”, ABC News, 31 October 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-31/wechat-data-cybersecurity-threat-china/10418874

- Nick McKenzie, Sashka Koloff, Mary Fallon, “China pressured Sydney council into banning media company critical of Communist Party”, Four Corners, 9 April 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-07/china-pressured-sydney-council-over-media-organisation/10962226

- Luke Buckmaster and Tyson Wils, “Responding to fake news”, Parliamentary Library Briefing Book, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook46p/FakeNews